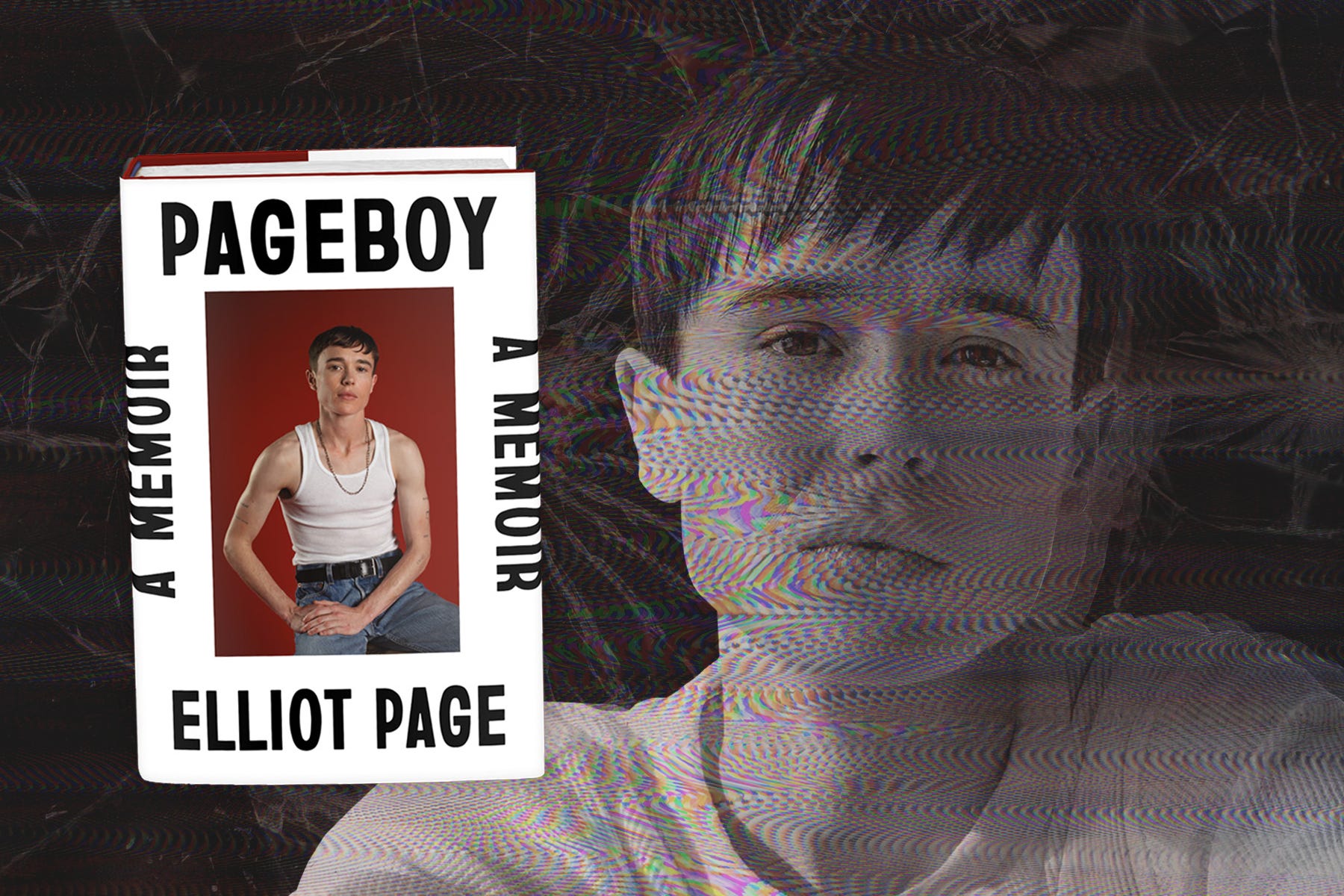

A De-Transitioner’s Review of Elliot Page’s ‘Pageboy’

Page has bought into the regressive notion that rejecting traditional femininity disqualified her from womanhood.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

Laura Becker | Funk⭐God is an American artist, writer, and speaker who shares her experiences with de-transition and healing through advocacy and activist work. Becker was featured in the documentary “No Way Back,” has been interviewed across media, and traveled internationally speaking on the harms of the “gender-affirming” model of care. Becker can be found on Substack, Twitter, and YouTube (@funkgodartist), and her “De-Trans Awareness” and “Free Thinker’s” collections of apparel and home goods are available in her Etsy store.

Elliot Page, the actress formerly know as Ellen prior to announcing in 2020 that she identified a transgender man, has written a memoir reflecting on her life experiences growing up as a young lesbian actress in Hollywood, and chronicling her recent transition. As a de-transitioned woman who once identified as a transgender man, I have been invited to review this memoir from my unique perspective of having a dual view of transgender and queer identity. The parallels to my own life experiences were stark, and I believe they can help provide useful insight into the social and ideological factors that shape contemporary transgender identities.

In this non-linear memoir, Page alternates between past descriptions of her childhood and young adulthood, and present day reflections on her life as a trans man. The book’s flow, however, felt disjointed, with chapters that seemed fragmented and meandering at times, degrading the immersive quality of what were otherwise compelling threads of a story about coming out as a lesbian.

Several patterns emerge from Page's life within the book, forming consistent themes originating in early childhood. Foremost among them is her romantic and sexual attraction to other women, and her shame and ambivalence around being gay, especially as a Hollywood actor. In the book’s initial pages, she vividly describes a meaningful lesbian relationship and how “Shame had been drilled into my bones since I was my tiniest self, and I struggled to rid my body of the old toxic and erosive marrow.”

This recurring sense of shame, rooted in her early childhood experiences as a gender-nonconforming girl, resurfaces throughout the book. Page described the incessant bullying from peers she endured as a child for being a “dyke,” “queer,” and a “faggot” in primary school growing up in Canada, and the heteronormative wardrobe expectations from TV and film producers as she began her acting career as an adolescent. Clothing was a particular source of pain for Page throughout her life.

Page’s description of her discomfort with, and resistance to, traditional girls’ clothing resonated deeply with me, mirroring many of my own experiences.

Readers learn the roots of Page’s love of acting, which she traces back to her feelings of alienation from her peers and family. She recounts countless hours of “private play,” a sanctuary where she could immerse herself completely in her imagination.

Those were some of the best times of my life, traveling to another dimension where I was…me. And not just a boy but a man, a man who could fall in love and be loved back… I often dreamed of being Aladdin. But it wasn’t for the rug, or the wishes, or the teeny monkey, but to know what it feels like to delicately touch a girl.

Much of Page’s childhood was fraught with a deep desire to express her love for and be close to other girls, in the way boys were permitted. She expresses her early confusion about her identity through a poignant anecdote from when she was four years old:

Primarily, I understood that I wasn’t a girl… I would try to pee standing up, assuming this to be a better fit for me… “Can I be a boy?” I asked my mother… “No hon, you can’t, you’re a girl,” my mother responded… “But you can do anything a boy can do.”

Reading about Page’s experience, I’m reminded of myself as a child on the autism spectrum. I knew logically I was a girl, but I didn’t feel that I belonged to girlhood. The other girls were pretty, agreeable, nice, while I was rowdy, clever, and messy. I felt a longing for boys to like me, but intuitively sensed that I was not the type of girl they would develop a crush on. This speaks to the experience of being gender non-conforming and watching your peers happily conforming to the same feminine fashion trends and allowing the boys to chase them around during play. I wanted to chase the boys, and I preferred wearing boy’s clothes because they were more comfortable.

Page recounted her early dysphoria surrounding clothing:

I’d throw a fit, a feeling of betrayal spreading through me as my mom tried to dress me. The sensation of tights squeezing my legs exacerbated all the discomfort that I couldn’t yet put words to. I didn’t grow out of this “phase” when I was supposed to…

During my period of identifying as trans, I too interpreted these childhood memories as confirmation of my trans identity, as preferences for opposite sex clothing, toys, and play are diagnostic criteria of gender dysphoria. However, once I came to the understanding that gender identity was an illusion, I realized that my penchant for comfortable clothing and a typical boy aesthetic didn't mean I wasn’t a girl. Instead, it signified my desire for a simplified grooming routine that was easy and practical. My sense of estrangement from other girls was not because I wasn’t one, but rather because I was autistic and had more individualistic interests which did not overlap with the average girl’s.

After Page’s central narrative of grappling with shame around being a lesbian, the prevailing theme in her life becomes her longing for parental approval and the attachment wounds she formed during early childhood, which were echoed countless times in subsequent relationships. Page was barely two when her parents divorced. She laments, “I’ve always found it strange that my mother and father had a baby. Me. Their relationship was in trouble by the time I came along…” Page’s father later married Linda, a woman who, despite becoming Page’s stepmother, prioritized her own children and groomed them, along with Page's father, to ostracize Page for her own amusement.

Of her father’s disloyalty to her, she states:

Around Linda that “love” evaporated. A transformation in the tone, the body, a face. A coldness, as if they’d conspired and teamed up, a frigid demeanor that made my eyes fall to the floor… My father did nothing, no protection. I yearned for time with my father, away from Linda… Linda did not like us spending time alone together, every time, without fail, it created friction.

Unfortunately, while Page was feeling alienated from her peers, she also felt rejected and unwanted at home.

Neither her mother nor father accepted her gender nonconformity, and Linda, her stepmother, often derided her with mocking comparisons to others. This sea of rejection resulted in a deep-seated self-loathing, typical among children in dismissive or emotionally abusive family systems. I relate to this childhood rejection, having experienced it myself from both peers and parents. While my father was overtly verbally, emotionally, and psychologically abusive—resulting in my development of complex PTSD—Page's experience of being unprotected by her father, of feeling isolated in her devalued self, and of finding solace in fantasy worlds resonated deeply with me. I can empathize with the shame Page felt, a consequence of incessant conditioning that she was neither acceptable nor appreciated for who she was.

The third major thread of her memoir involves early attachment wounds resulting in a lack of radar for red flags and dangerous situations involving adults and peers. At the age of 16, she suffered her first grooming experience by an older man she met online. As she entered the public eye in her television acting roles, this predatory man contacted her, and she, in her loneliness, formed a bond with him. The man began sexually harassing, stalking, and frightening her, to the point where on acting sets the entire cast and crew were put on alert for him. This incident sparked the inception of the fourth major theme in her story—her body dysmorphia.

After the sexual harassment, her disordered eating impulses intensified.

It isn’t as if I had no food thoughts before. They had started to pop up when puberty launched. I was filling out, growing breasts… Watching myself on-screen had not been a problem for me really, but as my body morphed, that changed. The more visible I became, the more I wanted.

The stalker’s actions ultimately escalated to a physical confrontation that led to his arrest, and Page found herself compelled to share this ordeal with her parents. Rather than finding comfort in their support and safety, she faced harsh rejection and blame from her father.

It was a relief to have him know… I was exhausted from the ceaseless state of disquietude… He was furious. Livid at what I had done, befriending an older man online when I was a kid. I went numb after that, his angry voice fading away, but will never forget those words. I’m going to come to Toronto and kick your ass. All the emails from my stalker paling in comparison.

This core rejection led to an overt and rampant manifestation of Page’s eating disorder, self-harm tendencies, and an internal critic filled with self-loathing.

Without any safe or trusted adult caregivers, she fell into a pattern of freezing when confronted with danger. She started spending more time on set, and moved away from her family to Hollywood while still underage. “Even though I preferred my path, my lack of healthy boundaries did not bode well.” She was groomed and assaulted by multiple directors and crew members, both male and female. She felt paralyzed and was unable to say no, so she endured their abuses.

At the age of 19, her traumas climaxed during and after filming a movie called An American Crime, where she played a true crime torture victim.

Moments in the film were unspeakably brutal. As a teenager, I did not have the skills to turn it on and off… My incessant, underlying need to flee, my new normal… Playing a character that was partially starved to death allowed me to lean into my desire to disappear, to punish myself… I’ll prove to you all that I need nothing.

Drawing from my own trauma-informed perspective, cultivated through my journey of healing and therapy, it’s clear that Page was conditioned from a young age to self-abandon. She believed herself simultaneously to be inherently unacceptable, while desperately hungering to be cared for and proved lovable. In her adult reflections, she appears aware of this, saying, “Hurting my body to that extreme must have been a cry for help, but when the help would come, it made me angry and resentful.Where have you been?”

This internal conflict resonates with my own experiences of going into survival mode from abuse. I acted out against others and myself as a form of self-rejection with the underlying hope of finding redemption. These activating behaviors left me mired in shame, creating a worldview based on instinctual self-rejection on which I could create a new worldview. I wanted to be seen, heard, loved, accepted, and rescued by my parents, teachers—anyone. But in despair, I realized that no one truly understood, and no one came. Out of frustration, I escalated my attempts at bonding through self-harm, cutting, overeating, neglecting hygiene, and making suicide jokes, but I only obtained more indifference or rejection.

The cycle of parental rejection, self-abandonment, and further rejection becomes glaringly obvious when you pinpoint its presence at every stage of your life. However, it’s profoundly difficult and overwhelming when you’re trapped within it. Page’s narrative encapsulates this struggle vividly. She describes a deeply felt attachment void, a feeling that amplified as her weight plummeted to a mere 84 pounds. “Loneliness had always been a staple for me, an inherent disconnect from my surroundings, a foundational disassociation. Lured away from my existence, I thought those around me wanted me to disappear, that I was preferred as an illusion.” I could have written this entirely myself.

Page’s return from the brink was getting her leading role in the critically-acclaimed film Juno, in which she played a sardonic, quirky, pregnant teen. She summoned the willpower to bring her eating disorder under control in order to perform the role.

It was a job where I felt comfortable, able to start from a grounded place, versus outside my body, trying to crawl back in…. I was wearing a fake belly but not being hyper feminized. For me, Juno was emblematic of what could be possible, a space beyond the binary.

It is hard to overlook the irony in such a passage. Page felt that because she was not forced to wear extensive beauty products and uncomfortable clothing, but only a pregnant woman’s belly, that this was an example of “a space beyond the binary.” Somehow the portrayal of pregnancy, the very epitome of femininity, didn’t cause her discomfort. Instead, it was the suffocating trappings of traditional femininity—the wardrobe, the grooming—that represented girlhood and womanhood to her, that she felt gender dysphoria about.

Reflecting on my own trans experience, a desire to escape the strictures of feminine beauty rituals was a large motivator for why I thought I should become man, but I also never had any maternal instinct. I believed, as many young women do, that being a mother was a social role of burden, a prison of labor, childcare, and little to no individual freedom that was granted to men by default. As I’ve grown older and matured, my perspective has shifted. Although the societal expectation of women to exclusively assume motherhood can be oppressive, I’ve come to recognize that childbearing and rearing are a meaningful gift, enhancing rather than diminishing individuality and personhood.

Page’s idea of what it means to be a girl or woman, or not to be a girl or woman, is regressive. She believes that enjoying boy’s toys or preferring comfortable clothes indicated she was not a girl, and that her attraction to women, like boys and men are, disqualified her from girlhood. This is both factually untrue and a dangerously misleading narrative to impart upon gender non-conforming young women. While being a lesbian is certainly an atypical female experience, it is nevertheless a distinctly female experience. Experiencing body dysmorphia, self-harming, and neglecting one’s female body does not mean it is a male body, yet these are the reasons Page consistently cites as evidence for being trans.

The book’s narrative is rife with descriptions of repeated patterns—failed lesbian relationships, often involving unavailable women, and herself unavailable to publicly acknowledge her sexuality as a gay Hollywood actress within a controlling and highly sexualized industry. By the book’s conclusion in 2023, she has divorced her wife, lived through the COVID lockdowns, came out as transgender, undergone testosterone therapy for over a year, and has undergone a double mastectomy to remove her breasts.

The lockdowns and marital separation offered her time for introspection:

I had spent years and years figuring out all the tricks to avoid my feelings, to exit my body, numb it out. But now, something was simmering, preparing to bubble over, I could feel it… This was not miracle water that sprang out of nowhere. This was a long-ass journey. However, this moment was indeed that simple, as it should be–deciding to love yourself.”

For Page, self-love involved removing her breasts to mimic the aesthetic of a boy, the boy she had longed to grow into as a child. She voices gratitude for her medical care, while expressing frustration at the ambivalent responses her transition has garnered: “As a trans person, and a public one, the sensation is that I’m always pleading for people to believe me, which I imagine most trans people relate to. Tired of the wink and nod.”

In wrapping up this review, I am left wondering: what exactly does she want us to believe? Are we expected to accept that she has always been, or has transformed into, a man? Are we to believe that she is no longer a woman, an actress, a lesbian? Or does she simply want us to acknowledge her struggles with her body and identity as Ellen Page? That her pain is real, that her joy is real, now that she has masculinized her body?

As someone who has detransitioned and survived complex trauma, I want to say: Your pain is real, Ellen. Your joy is real. I believe your experiences. But I disagree that you are a boy, or a man. Despite my own mastectomy scars, you and I will always be women, and that is neither an insult nor a judgement. It’s just life.

In sum, this book was an easy and quick read, providing compelling accounts of the lesbian experience, insights into the pros and cons of child acting, and a peek into the mind of someone grappling with gender dysphoria. I would endorse this as a relatable book for lesbians, or those who are fans of Page’s work. However, I would not recommend this book as a source of healthy information or role modeling for young people with gender dysphoria. Page does not appear to have had dual diagnosis in therapy, which would exclude comorbidities for gender dysphoria before moving forward with transition as the ultimate treatment plan. She had no safeguarding throughout the process and made the decision rather quickly after her divorce, amidst a pandemic, and at the dawn of being open with her therapist.

In the closing pages of her memoir, she expresses joy at seeing 15 and 16 year old trans-identifying kids in public and endorses their decisions. However, I must remind readers that Page transitioned in her 30s, after having undergone full pubertal development and accumulated life experiences prior to making her decision. Encouraging children to transition without a similar privilege of perspective is unethical. While I genuinely wish Elliot Page all the best, she should not be looked to for guidance on how to healthily manage one’s gender dysphoria, especially for children.

Reality’s Last Stand is 100% reader-supported. If you enjoyed this article, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below. Your support is greatly appreciated.

I just want the insanity to stop. The mutilation and medication. The predatory men in women's and girl's spaces, prisons, sports, jobs. Someone make this nightmare go away.

Thank you Laura Becker for standing up to Page’s narrative. She’s a cultural force right now and the trappings of her narcissism, her need for attention might lead young people into regretful, permanent medical treatments.