Six Books for Students of Evolutionary Biology

Books that encapsulate the history, marvel, and debates within the field.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

Note: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

While the appeal of any subject is somewhat subjective and dependent on the interests and curiosities of the individual, I believe that evolutionary biology holds a particular fascination that, for me and many others, makes it the most intellectually satisfying subject in the world. It offers an unprecedented window into the past, a fresh lens to view the present, and a speculative telescope to glimpse the future.

Understanding life’s historical narrative is a central pillar of evolutionary biology. It tells a story filled with mystery, drama, survival, and adaptation, spanning billions of years. Evolutionary biologists get to step into the shoes of a time-traveler, retracing the footsteps of ancient organisms and piecing together how evolution has shaped the living world. It’s an awe-inspiring journey that humbles and simultaneously broadens our perspective on life.

While the principles of evolution have immense real-world applications that impact our everyday lives, such as understanding disease origins and resistance, thus guiding medical breakthroughs, my own interest in evolution stemmed from its ability to grapple with—and actually get answers to—profound existential questions. Questions like “Where did we come from?”, “How did life begin?”, and “How did we become who we are?” are part of the subject’s essence. An evolutionary framework allows us to seek answers about our origins and understand the roots of our behaviors, instincts, and cultural tendencies.

Evolutionary biology is therefore not just a branch of science; it’s a way of understanding the world and our place in it. It opens up a universe of inquiry that is as vast as it is deep, offering unique intellectual satisfaction.

In light of this, you might now be wondering how to deepen your exploration of this remarkable field. To help guide you, I’ve carefully curated a list of six books that encapsulate the history, marvel, and debates within the field.

This list is not for the total beginner, but rather for the students of biology who is interested in pursuing a career as an evolutionary biologist. If there is interest, I can put together a list of introductory books to the subject as well that assume no prior knowledge of the field. Please let me know in the comments if that would be welcome.

Until then, enjoy the journey!

Sincerely,

Colin Wright

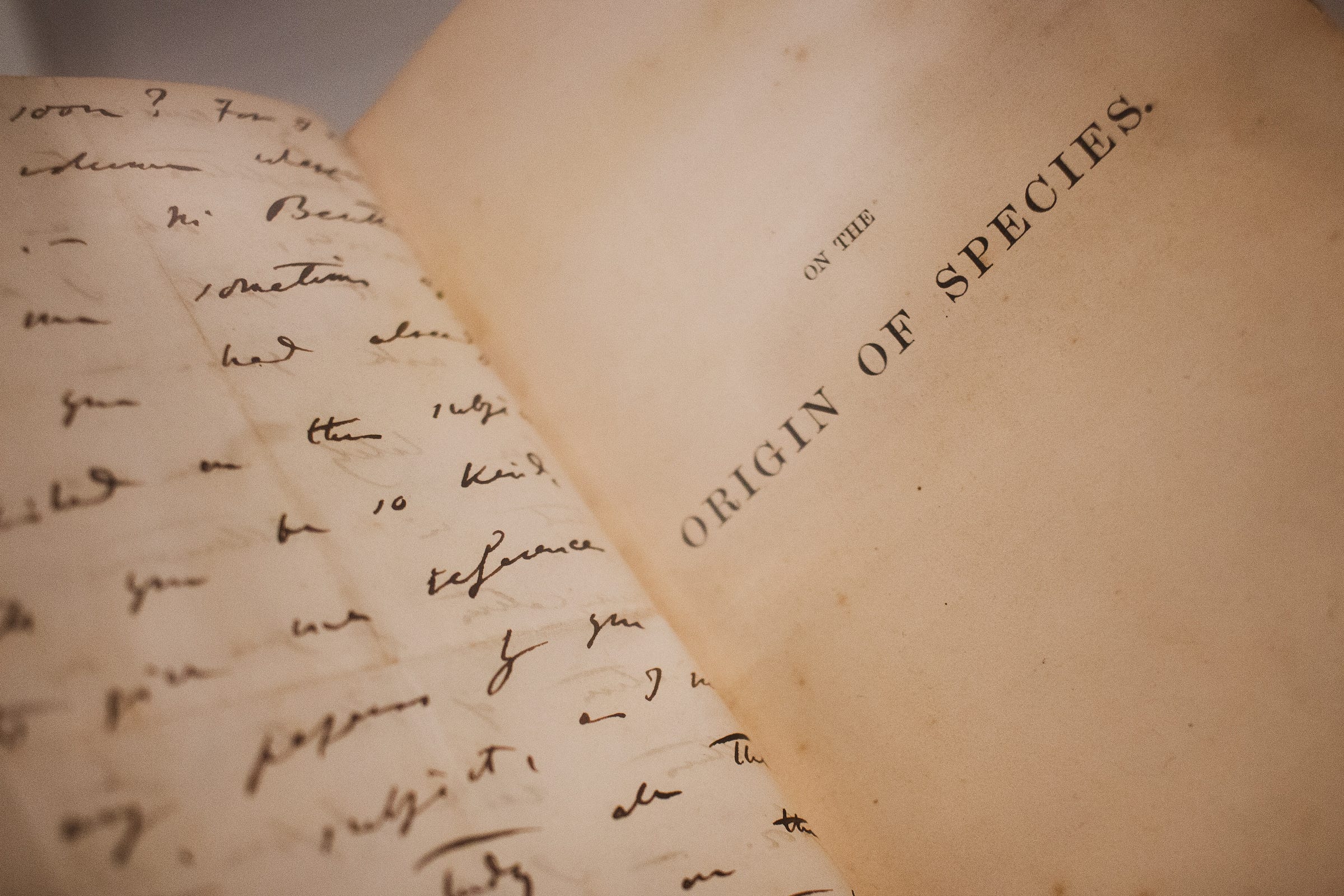

1. On the Origin of Species (1859) | Charles Darwin

This one is a no-brainer, yet it’s shocking how few modern students of evolutionary biology have read it. Most students don’t appreciate how much of modern evolutionary research stems from Darwin’s many profound musings made in this book.

On the Origin of Species is nothing short of a groundbreaking work in the field of evolutionary biology. It presents the theory of evolution through natural selection, which is based on the idea that species evolve over time due to the differential survival and reproduction of individuals with advantageous traits.

In his book, Darwin outlined his key arguments such as the existence of variation in nature that occurs both within species and between species. This variation, coupled with limited resources, meant that organisms are engaged in a constant struggle for survival and reproduction. In light of this, individuals with advantageous traits are therefore more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on these traits to their offspring. Over time, this blind process leads to the evolution of species.

Darwin’s work was far from merely theoretical, and his book sets a high standard for rigorous scientific argumentation rooted in empirical evidence. He does this by drawing parallels between the process of natural selection and artificial selection (selective breeding) in domesticated animals, showing that humans have harnessed the power of selection to shape the traits of both animals and plants. He drew on evidence from biogeography, or the distribution of species across different regions, by demonstrating that species from the same area tend to be more closely related than species with similar habitats but different geographical locations. He showed how the fossil record supported the idea of gradual evolution and the extinction of species over time. He used comparative anatomy to show evidence for common ancestry and evolutionary relationships.

Darwin laid the groundwork for our modern understanding of evolution, and reading the original text provides insight into the development of these ideas and the historical context in which they emerged. Modern students of evolution can benefit greatly from examining the original observations and arguments that shaped the field.

On the Origin of Species is a vital read for any modern student of evolutionary biology.

2. The Growth of Biological Thought (1982) | Ernst Mayr

Ernst Mayr is a total badass. He lived to 101 years old (1904-2005) and was active in the field for over 80 years. His final book, What Makes Biology Unique?, was published in 2004 when Mayr was 100 years old! In addition to his longevity, he made major contributions to the fields of evolutionary biology, systematics, and ornithology, but is best known for his work in developing the modern synthesis of evolutionary theory, which integrated genetics, paleontology, and systematics.

Mayr also formulated the widely accepted Biological Species Concept, which defines a species as a group of interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups. This concept has been pivotal in helping scientists better understand and classify the diversity of life on Earth. He also proposed the idea of allopatric speciation, which is the process by which new species evolve due to the geographic isolation of populations.

Mayr was a prolific writer and communicator of science, and his book The Growth of Biological Thought (1982) is a shining example of that. The book is comprehensive and scholarly, and outlines the history and development of biological thought from antiquity to the modern era. It is divided into three major sections: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance, which correspond to taxonomy, evolutionary theory, and genetics, respectively. Through these sections, Mayr explores the major ideas, controversies, and breakthroughs that have shaped the field of biology.

If I were still in academia, this is a book I’d force all my graduate students to read, as it provides overarching context regarding the intellectual debates and controversies that have marked the history of biological thought, which is essential for anyone seeking a deep understanding of the development of the foundations evolutionary biology as a discipline and its integration with related fields.

Mayr’s work has helped shape the field in major ways, and his ideas continue to inform researchers today. This is simply a must read for students of evolution.

3. Essays On Natural History | Stephen Jay Gould

The late Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould is a controversial figure in evolutionary biology, both because of his science and his politics. Some would argue that his politics tainted his science, and to some extent I’d have to agree. Politics aside, Gould made substantial contributions to how biologists think about evolution.

One of Gould’s biggest contributions to science was his notion of Punctuated Equilibrium, which he along with Niles Eldredge proposed that suggests evolution occurs in rapid bursts of speciation over short time scales, followed by long periods of stability or “stasis.” This concept challenged the traditional view of gradualism in evolution, suggesting that the fossil record’s apparent gaps might not be an artifact of poor preservation but instead evidence that most speciation events occur during periods of rapid change that are unlikely to be captured in the fossil record.

Gould and Eldrege’s theory was hotly debated, with its main detractors being Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett, who claimed, among other things, that Punctuated Equilibrium did not overturn any traditional notions of gradualism in evolutionary biology, but simply emphasized the pace at which gradual evolutionary change occurs. The book Dawkins vs. Gould: Survival of the Fittest by Kim Sterelny did an excellent job providing an objective overview of the battleground ideas in this longstanding debate.

Gould was also known for emphasizing the role of non-adaptive processes in shaping the history of life. By discussing examples like the panda's thumb and spandrels in architecture, Gould challenged the prevailing view that natural selection was the sole driver of evolution, highlighting the importance of considering other mechanisms, such as genetic drift and developmental constraints for understanding the diversity of life.

My favorite thing about Gould, however, was his writing ability. While his scientific papers as well as his massive tome The Structure of Evolutionary Theory were often quite dense and, in my opinion, overly verbose and pretentious sounding, his popular science writing was nothing short of phenomenal. His natural history essays are exemplars in clear and engaging science writing, and I often used individual essays as assigned reading for classes I taught while in graduate school.

Fortunately, Gould’s many essays were published across 10 books. However, I believe that the first three books of his natural history essays —Ever Since Darwin, The Panda’s Thumb, and Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes—are the absolute best and should be considered required reading for any student of evolutionary biology. Gould’s awe-inspiring essays played a significant role in my decision to pursue a career as an evolutionary biologist and science communicator, and I hope they will continue to educate and inspire new generations of evolutionary biologists.

4. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995) | Daniel C. Dennett

Daniel C. Dennett is an American philosopher, writer, and cognitive scientist known primarily for his research on philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science.

I first learned about Dennett due to my involvement with New Atheism in the late 2000s and early 2010s, as he was one of New Atheism’s anointed “Four Horsemen,” which in addition to Dennett included evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, philosopher Sam Harris, and author Christopher Hitchens. I read and thoroughly enjoyed Dennett’s book Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. It wasn’t until I formally decided to begin pursuing a career in evolutionary biology that I became more interested in Dennett’s work on evolutionary theory.

I remember starting Darwin’s Dangerous Idea thinking it would be an easy read that mostly rehashed the history of how Darwin came to his theory of evolution by natural selection, how it worked, and perhaps offered some insightful philosophical implications of natural selection that I hadn’t considered before. Boy was I wrong.

Darwin’s Dangerous Idea remains one of the most difficult and brilliant books on evolution I have ever read. However, its difficulty lies not in its writing, which is fantastic, but in managing to keep track of all the profoundly deep insights Dennett synthesized from related fields and philosophical concepts. Every paragraph is incredibly information rich, and you need to remain totally focused to reap its benefits.

In the book, Dennett argues that Darwin’s idea of natural selection is an incredibly powerful and potentially dangerous idea because it fundamentally challenges traditional human-centered views of the world. He calls it a “universal acid” that dissolves traditional beliefs about the special place of humans in the universe, our moral significance, and even our sense of purpose.

One of my favorite ideas Daniel Dennett introduces is the concept of the “Library of Mendel” as an analogy to help explain the power of evolution and natural selection. The Library of Mendel is a fictional library that contains a vast collection of books, each representing a unique organism. The books are generated through a process that mirrors genetic variation and natural selection. Dennett uses the library metaphor to highlight how evolution works like an algorithmic process, gradually refining and improving the “books” (organisms) over time. As the library grows, books are subjected to a “design process” that tests their fitness in a given environment. Books that are better suited to survive and reproduce are more likely to be retained and further refined.

In this metaphor, the “authors” of the books are not intelligent designers but rather the processes of random mutation and natural selection, and serves to illustrate the power of Darwinian evolution in generating immense complexity and adaptation without the need for an intelligent designer.

Dennett also introduces the idea of “Design Space,” which is an abstract, multidimensional space that represents all possible design solutions to any given problem. The process of evolution can be thought of as a sort of “search” through this space, with natural selection acting as a blind yet remarkably efficient designer, discovering and refining increasingly effective adaptations over time.

I could go on and on about the various insights contained within this book but, needless to say, I can’t imagine any student of evolutionary biology not being blown away by this book. It will help you grow as an evolutionary thinker by opening many doors to the implications of natural selection you never would have imagined.

5. The Selfish Gene (1976) | Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins is one of my intellectual heroes and had the biggest influence on my decision to become an evolutionary biologist. Dawkins was a student of Nikolaas Tinbergen, the Nobel Prize winning Dutch biologist widely viewed as the father of modern ethology, or the study of animal behavior. It is no coincidence that I studied animal behavior for my PhD, though my focus was on collective, rather than individual, behavior.

I didn’t start by reading Dawkins’ books on biology. The first book of his I read was The God Delusion, followed by his more popular science books such as The Ancestor’s Tale, The Blind Watchmaker, and Climbing Mount Improbable. It wasn’t until I had a solid grounding in genetics and evolutionary thinking that I decided to give The Selfish Gene a try. It did not disappoint.

The Selfish Gene is a groundbreaking and influential work in the field of evolutionary biology that aims to provide a new perspective on the process of evolution, focusing on the gene as the central unit of natural selection. Dawkins argues that individuals should be thought of as merely “survival machines” constructed by genes to ensure their own replication and transmission to future generations. The book’s central thesis is that organisms are driven by the sole purpose of replicating their genes, and that all aspects of their behavior can be understood as strategies to maximize this replication.

Throughout the book, Dawkins employs numerous examples and thought experiments to illustrate his points, drawing on various fields such as ethology, game theory, and population genetics. Dawkins also introduced the concept of “memes” in this book, which are units of cultural transmission akin to genes. He also proposed and the concept of the "extended phenotype," which posits that the effects of a gene can extend beyond an organism’s body and influence its environment.

A serious student of evolutionary biology simply must read this book to gain a solid understanding of the gene-centered view of evolution and to become familiar with foundational ideas that underpin modern research in the field.

6. Unto Others (1998) | David Sloan Wilson

David Sloan Wilson is an evolutionary biologist whose primary area of research and interest is multi-level selection theory, otherwise known as “group selection.”

I included this book because I think it provides a great contrast to ideas many biologists appear to take for granted. In biology, “units of selection” has been a topic of considerable debate. Traditionally, the focus was on the individual organism as the primary unit, or the gene as proposed by Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene (mentioned above). According to this perspective, evolutionary pressures act to optimize the survival and reproductive success of individuals or genes.

However, David Sloan Wilson, alongside others, argues for the possibility of selection operating at various hierarchical levels of biological organization, such as genes, cells, individuals, groups, and even species. Such selection can in principle promote traits that may not be beneficial or may even be harmful at a lower level, as long as they increase the fitness at a higher level. Thus, certain traits may evolve because they enhance the survival or reproductive success of the group, even if these traits might be costly to individuals within the group.

To call this “highly controversial” would be an understatement. This was fiercely debated when I was in graduate school between 2013 and 2018, and this was by no means the peak of conflict between these two schools of thought. The individual selectionists insist that all “group selection” can be explained fully within the models of individual selection. But group or “multi-level” selectionists argue that there are at least some traits that occur at the level of the group that simply can’t be reduced down to selection operating at lower levels.

I believe that David Sloan Wilson is the best expositor of multi-level selection theory, and he does so in an extremely accessible way in his book Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior.

The book is divided into two main sections. The first section, titled “The Evolution of Altruism,” focuses on the theoretical aspects of group selection and its role in the evolution of altruistic traits. Wilson provides a thorough analysis of the various theories of altruism, including kin selection, reciprocal altruism, and group selection, examining their implications and limitations. He then presents empirical evidence supporting the idea that group selection can be a potent force in the evolution of cooperative behavior.

The second section, titled “The Psychology of Altruism,” delves into the psychological aspects of altruistic behavior. Wilson examines the cognitive and emotional mechanisms that underlie unselfish acts, exploring how they have evolved in response to selective pressures at both the individual and group levels.

To be a good evolutionary biologist, and scientist generally, you must know the history of ideas in your field. Often certain aspects of evolution, like a gene-centered view of selection, are presented as settled science. And while the individual or gene-centered view may in fact be correct, it is important to understand the best arguments against it. Unto Others is therefore an essential read for students of evolutionary biology interested in learning about challenges to traditional views on the nature of natural selection.

Reality’s Last Stand is 100% reader-supported. If you enjoyed this article, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below. Your support is greatly appreciated.

I would love a guide to books for a non biologist.

Great list. I would add Dawkins’s The Extended Phenotype, an excellent “sequel” to The Selfish Gene.