The Sex Wars Conference

Two sides in the debate about sex differences squared off for two days in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Here’s what happened.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

Diana Fleischman is an evolutionary psychologist, writer, and interviewer. Check out updates about her work @sentientist

Because of the flaming culture wars, feminists and others who disagree about the nature of sex or sex differences often ascribe significant harms to researchers who claim that sex is binary or who acknowledge biological sex differences. These perceived harms include oppression, inequality, and even murder and suicide. As a result, many influential voices in the sex difference debate rarely engage in dialogue. This context made “The Big Conversation”—an October conference that brought together a diverse group of feminists, evolutionary psychologists, biologists, and neuroscientists—such a remarkable event. The rarity of such a meeting was highlighted by the cancellation of a panel on sex differences at an annual anthropological conference just a few days before.

People who had sniped at each other for years through academic papers and social media not only shared stages and panels, they broke bread together. Attendees on all sides of the issue held my baby, whom I brought along. The fear of meeting ideological opponents often leads to the expectation of hostility in person, but what’s worse is that you often will come to like them!

The Big Conversation took years to come together. It was organized by sex difference expert Marco Del Giudice and Paul Golding of the Santa Fe Boys Foundation. This foundation is dedicated to exploring how to help boys and young men and was the event’s sponsor. The conference featured 16 talks and 5 discussion sections. The entire conference is available for viewing (for free!) on the Santa Fe Boys Foundation website.

The Gender Equality Paradox

A central questions in sex difference research concerns the origins of differences between men and women. Are these differences primarily the result of socialization, culture, and stereotype effects, or are these differences largely innate or biological? We can call these perspectives, as Carole Hooven did during her talk, the strong socialization view and the strong biology view, respectively. Many of the conference attendees, like Gina Rippon, Cordelia Fine and Daphna Joel, endorse the strong socialization view of sex differences, arguing that men and women are innately psychologically similar but are driven into different roles by cultural forces and socialization. This perspective sparks controversy surrounding discussions on biological sex differences because its proponents argue that legitimizing and publicizing sex differences creates them where they did not exist before.

One way to examine the validity of the strong socialization view is by comparing the differences between men and women around the world and across cultures. The disparity in earnings between men and women, as well as the underrepresentation of women in high-status, high-paying STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) careers has been of major concern for the feminist project. Commentary on women’s capacity for STEM have sparked controversies over the years, such as those involving Larry Summers and the infamous Google Memo. However, there are signs of progress. For instance, Claudia Goldin recently became the first woman to win the Nobel Prize alone in her field for her work on gender pay gaps just a few days after The Big Conversation. Goldin’s research is compatible with the idea that pay gaps result from women’s choices rather than discrimination.

During a panel discussion with prominent feminists, David Geary laid out the strong socialization view (here), stating, “as societies become more egalitarian that psychological sex differences would disappear or become highly similar.” Unfortunately, he says, this prediction “has been disconfirmed.” In his paper on the Gender Equality Paradox, Geary demonstrated that gaps in STEM fields are actually more pronounced in gender egalitarian countries (as are gaps in personality). This is the opposite of what strong socialization view would predict, which generated considerable discussion throughout the conference.

For example, Cordelia Fine speculated in her presentation that these differences exist “because wealthy capitalist economies provide a richer environment of gender essentialist mindshaping.” Similarly, Gina Rippon proposed in her talk that stereotypes about men being better at math are stronger in more gender egalitarian countries. However, Rippon assumes that the stereotypes cause the gender gap, when, given what we know about the science of stereotypes, it’s more likely that the gender gap causes the stereotypes. The notion that stereotypes significantly impair women’s math performance hasn’t been borne out by evidence.

Later, Rippon said that countries considered gender egalitarian countries should be referred to as “allegedly gender egalitarian.” I agreed with William Costello’s take here that “had the sex differences diminished in these gender egalitarian countries, social role theorists would have been shouting it from the rooftops.”

Sex Differences and Sexual Selection

Advocates of the strong biological view agree that the sex binary is real, sex differences are mostly biological, and evolution has exerted different selection pressures on men and women. These ideas serve as an engine for hypothesis generation. In contrast, it’s more difficult for those who simply say “it’s complicated” or insist that all humans are a “mosaic” of male and female attributes to make falsifiable predictions.

In his talk, David Geary made testable predictions about how sex differences should vary under different environmental conditions according to sexual selection. Exaggerated traits, like the peacock’s tail, are indicators of health and vitality. A peacock in a favorable environment can more easily grow a large, symmetrical, and vibrant tail, whereas one in poor conditions may develop a smaller, asymmetrical, and duller tail. On the other hand, we shouldn’t expect a female peacock’s (peahen) feather quality to be so tightly linked to environmental conditions since it did not evolve as a quality signal.

Over recent decades, improvements in health, nutrition, and sanitation have led to increases in average height and intelligence. Geary hypothesized that in better environments, sex differences in traits influenced by sexual selection would also become more pronounced. For example, men are taller than women because of a history of men competing with other men in which taller men had a competitive advantage. So, as nutrition improves, men’s height increases more than women’s. In 1900, the average British man was 11 cm taller than the average woman but he was 15 percent taller than the average woman in 1958, an increase of 36 percent. This pattern is observed globally, with better conditions widening the gap between male and female height. Geary also presents similar results for cognitive and behavioral sex differences. As conditions improve, women show better episodic memory and men show better spatial cognition. Boys who are nutritionally supplemented engage in more rough and tumble play (practice for fighting—demonstrated here in Hooven’s talk), while there is no change in aggression for girls. This is also why we should not expect STEM gaps to narrow as environments get better: in such environments men’s aptitudes will likely increase compared to women.

Natural Experiments

At one point during a panel discussion, moderator Scott Barry Kaufman asked all the participants “what evidence would change your mind?” regarding the origin of sex difference. Cordelia Fine and David Puts, who hold opposing views in the sex differences debate, agreed that an “impossible experiment”—where boys are socialized as girls and vice versa—would sway their opinions.

However, there are some natural experiments where biology and socialization are decoupled that challenge the socialization hypothesis. One famous example is “Guevodoces,” which means “eggs at twelve” from the Dominican Republic. These boys are born with genitals that appear female, and they are raised as girls. However, at puberty, their testicles, or “eggs” emerge (here is one of their stories). Importantly, they are also exposed to normal masculinizing hormones in utero. According to the socialization hypothesis, these males should have difficulty psychologically embodying manhood, but they don’t. The Guevodoces almost invariably grow up to be heterosexual men.

Another example of a mismatch between hormonal influence and socialization is seen in congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Females with CAH are exposed to increased prenatal androgens, which are masculinizing hormones. CAH girls exhibit more masculine interests and better (more masculine) spatial ability than unaffected women. There are even studies comparing CAH girls to their unaffected sisters, providing a clever way to control for family upbringing.

Cordelia Fine attempts to explain the masculinization of CAH women by saying that their masculinized appearance, genitals, and the “priming of expectations of masculinity in clinicians, parents, and the girls and women themselves” might contribute to this phenomenon. While Fine deserves credit for even bringing up CAH women, this seemed like another instance where proponents of the strong socialization view come up with a post-hoc justification for the data they see rather than acknowledging it as evidence against their hypothesis. So far, all natural experiments involving a mismatch between socialization and prenatal hormone exposure lean towards supporting the strong biology view.

In his talk, David Puts introduced another condition bolstering the strong biology view: Idiopathic Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism (IHH), which also decouples socialization and biology. Males with IHH are exposed to less prenatal androgens, but the condition remains undiagnosed until puberty. This means there is no opportunity for doctors or parents to treat them differently or socialize them less like boys based on a diagnosis. Supporting the role of prenatal androgens (strong biology), males with IHH are more likely to be bisexual or attracted to other men. They also exhibit more gender nonconformity (see paper). IHH males report a higher likelihood of playing with girls, enjoying feminine toys and games, and identifying more with feminine careers and roles. Here is Fine responding to Puts’ talk.

Sex and the Brain

Four out of 16 talks during the weekend were about the differences (or lack thereof) between male and female brains. This garners significant attention due to a widespread intuition people have that structural differences between men and women’s brains must signify something innate. However, in practice, structural scans of people’s brains like MRIs can’t tell you much. For example, just looking at structural brain imaging can’t differentiate between between a childless female engineer, a woman who killed her husband, and a suburban mom with 6 kids. This doesn’t imply that no differences exist among these individuals; rather, it highlights the limited resolution of brain scans in revealing such distinctions.

The regular refrain of “neurofeminists,” like Lise Eliot, is that there is no single brain region that can discriminate a male brain from a female brain. This is a slippery debate tactic because a computer algorithm can predict a person’s sex from a brain scan with 93 percent accuracy, and brain size is one of the main ways you can distinguish male and female brains (accordingly, classification accuracy drops to 60-70 percent if brain size is controlled for).

One of the most contentious issues in sex difference research is the difference in brain size, with studies indicating that men’s brains are 11 percent larger than women’s. Neurofeminists tend to downplay this difference, claiming that it is merely a result of men’s larger body size and should therefore be disregarded. However, in Marco del Giudice’s talk he outlined some intriguing implications of this size difference, including, most contentiously, that men have higher IQ than women.

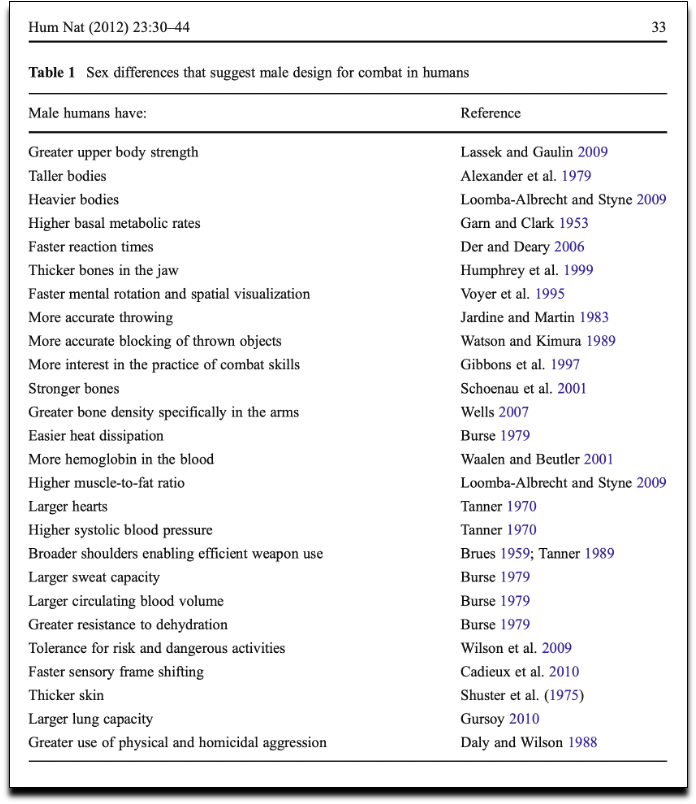

del Giudice advanced a new hypothesis about why men have larger brains: risk-taking behavior. Men tend to engage in more heroic and aggressive activities, including big game hunting, risk-taking, and physical altercations. These activities, which increase the risk of brain injury, have been a part of men’s evolutionary history. Impaired cognitive function due to brain injury is maladaptive. To maintain cognitive function after a potential injury, men may have evolved larger brains as a protective adaptation. Comparing men’s and women’s physical traits (as outlined in the table below), men appear to possess several characteristics enhancing their resilience to physical injury. del Giudice suggests that, like other adaptations, increased brain volume in men compensates for their heightened aggression and risk-taking. Supporting this hypothesis, evidence shows that men generally have a better recovery from traumatic brain injuries and a lower risk and progression rate of Alzheimer’s disease compared to women.

Should We Make a Nonbinary World?

Most of the time, the strong socialization view and the idea that men and women are similar are packaged together with an ideology. This ideology asserts that the world would be a better place if we stopped categorizing humans as male or female.

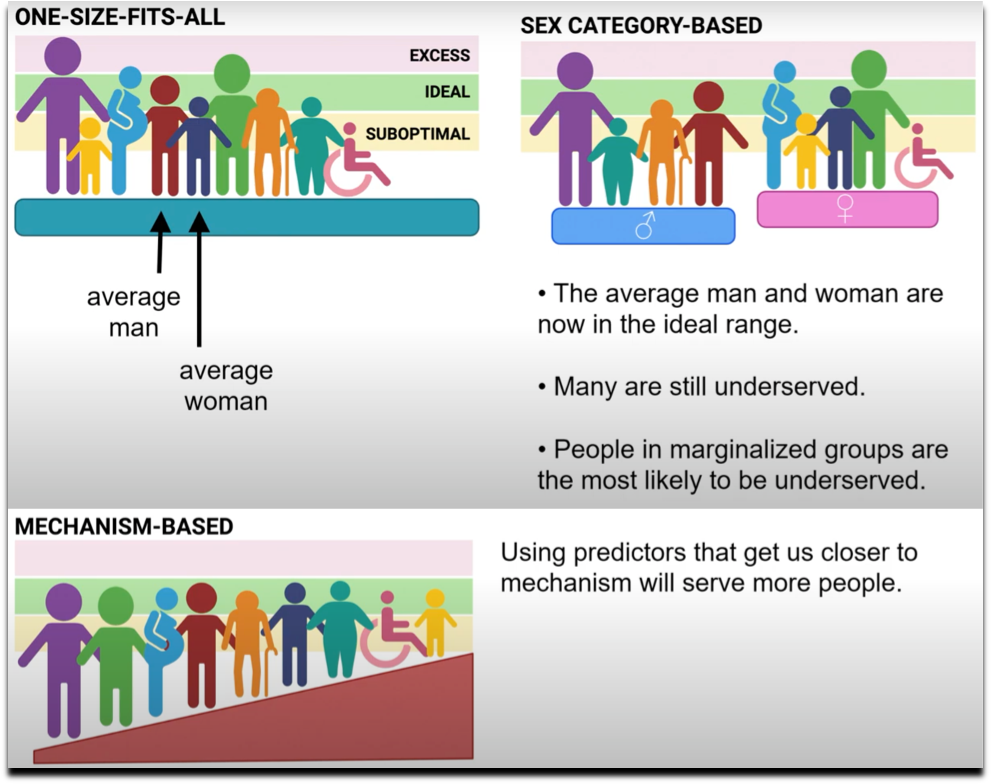

In her talk, Donna Maney argued that we should stop talking about males and females in medicine. She posited that while a one-size-fits-all approach to dosing a drug might be suboptimal, dividing people into male and female categories primarily harms marginalized groups such as obese, nonbinary, transgender, or pregnant people. Instead, Maney proposed considering factors like circulating hormone levels. My critique of Maney’s approach is that decision making based on sex categories is more practical than the one-size-fits-all method and simpler than a mechanism-based approach. We all know our sex but may not be aware of specific details like our circulating estradiol levels. Carole Hooven countered that Maney’s approach overlooks how women’s physical and psychological traits synergize in an evolutionary strategy linked to egg production. Moreover, even when a drug affects males and females differently, we might not know or be capable of measuring every relevant factor, such as hormone levels, bone density, behavior, and environmental differences that influence responses to drugs or treatments.

Daphna Joel was one of the most forceful voices in her opposition to the sex binary or gendered socialization. “I’m trying to advance a world without gender,” she said. “I want a society in which I am not expected to do somethings or not do some things based on the genitalia I have.” Joel wants male and female to be categories we think about as little as “blue-eyed” or “left-handed.” I admired her forthrightness, especially since many conference attendees seemed hesitant to fully express their views about how much better the world would be without a binary sex classification scheme.

However, as I pointed out above, it’s questionable whether changing the way we socialize children and adults would have a large effect on their relative masculinization and feminization. Moreover, while most people would concede that attempting to socialize children in a gender-neutral manner is nearly impossible, few seem to have seriously considered whether a genderless world is something truly desirable. Would such a world actually increase the total sum of human flourishing, satisfaction, or happiness?

Research on women’s happiness and depression is tricky, but there is good evidence that women place higher value on family time and less on work compared to men. Despite increased gender equality, women’s wellbeing hasn't shown significant improvement. Interestingly, progressive men and women, who are least likely to believe in and adhere to traditional gender roles, are less happy than their conservative or religious counterparts.

The poor mental health of people who identify as “non-binary” is particularly relevant when considering the implications of attempting to erase or stigmatize innate sex differences. In light of this, I asked the panel why we should attempt to do away with traditional sex roles and the sex binary. David Schmitt said that gender egalitarian cultures weren’t making women happier because they were still expected to fulfill dual roles of work outside and within the home. Daphna Joel countered this by pointing out that women are generally happier in gender-egalitarian countries compared to those with strict gender roles, like Afghanistan and Iran.

Downplaying innate sex differences and discouraging gender roles are often viewed as a vital steps toward greater equality between men and women. However, as Colin Wright pointed out here, while he agrees that people should have the right to self-expression, any observed disparities between men and women are invariably interpreted by the strong socialization camp as de facto evidence of coercive gender role socialization. Therefore, efforts to eradicate all gender disparities could become as restrictive and coercive as the traditional roles they aim to replace.

Overall, The Big Conversation admirably modeled constructive disagreement. I was continually impressed by the participants’ efforts to find common ground. While it’s uncertain if any minds were changed, the panelists undoubtedly gained a better understanding of opposing viewpoints, which will hopefully inform their future work.

Reality’s Last Stand is 100% reader-supported. If you enjoyed this article, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Thanks for providing a summary of the conference! My main takeaway is that people are very hung up (again) on the nature/nurture dichotomy when it comes to sex differences. It seems obvious that most of the development of human individuals is an interaction between innate tendencies and environmental influences. Arguments that polarize these factors are usually driven by emotional concerns arising from political and cultural pressures outside of the scientific debate. Sex-based discrimination is one of these. It would be helpful if both the scientists and the advocates for various interest groups could stop using arguments about sex differences to support positions that favor or oppose discrimination, which continues to be a real thing in our society.

Interesting to take on feminists as opposed to TRA's, but I understand the importance of being able to talk about these issues. There was a common 19th century phrase, "Classics for gentlemen, science for ladies." Computer engineering was initially thought of as a woman's job. And there have been massive increases in women in STEM, because of a concerted cultural effort to create room for them. I don't understand why these points are so often ignored. Of course there are average behavioral differences, and of course some of them are rooted in biology. But why ignore the cultural?

"In 1970, women made up 38% of all U.S. workers and 8% of STEM workers. By 2019, the STEM proportion had increased to 27% and women made up 48% of all workers.

Since 1970, the representation of women has increased across all STEM occupations and they made significant gains in social science occupations in particular – from 19% in 1970 to 64% in 2019.

Women in 2019 also made up nearly half of those in all math (47%) and life and physical science (45%) occupations."