The Zombie Study Behind the ‘1% Regret’ Myth for ‘Gender-Affirming’ Surgery

A critical look at the paper behind one of gender medicine’s most repeated false statistics.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

Dr. Colin Wright is the CEO/Editor-in-Chief of Reality’s Last Stand, an evolutionary biology PhD, and Manhattan Institute Fellow. His writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Times, the New York Post, Newsweek, City Journal, Quillette, Queer Majority, and other major news outlets and peer-reviewed journals.

One of the biggest controversies in the debate over pediatric “gender-affirming care” is the experimental nature of its most invasive interventions: puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries. Recent systematic reviews in Europe—most notably the UK’s Cass Review and a comprehensive new report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—have concluded that the quality of evidence supporting these treatments is very low. Meanwhile, the risks are well documented: sterility, sexual dysfunction, impaired brain development, and irreversible physical changes.

You would think that something this serious—especially for kids—would be backed by strong, long-term clinical data. But that’s not what’s happening. When critics raise concerns about the lack of good evidence, supporters often change the subject. Instead of defending the science, they focus on an emotional claim: regret is incredibly rare. If nearly everyone is happy afterward, they argue, the treatments must be working.

You would think that something this serious—especially for kids—would be backed by strong, long-term clinical data. But that’s not what’s happening. When critics raise concerns about the lack of good evidence, supporters often change the subject. Instead of addressing the lack of positive evidence of benefit, they pivot to an emotionally resonant claim: that regret is exceedingly rare. If nearly everyone is happy afterward, they argue, the treatments must be working.

This rhetorical sleight of hand—substituting low regret rates for proof of benefit—has proven remarkably effective. It is frequently claimed that fewer than 1 percent of patients who undergo “gender-affirming” surgery come to regret it. This talking point is everywhere, deployed in courtrooms, legislation, news segments, and policy debates as proof that these surgeries are safe and effective.

What most people don’t know is that this widely repeated claim comes from a single paper published in 2021: “Regret after Gender-affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence” by Bustos et al. The study appeared in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, a pay-to-publish version of the flagship journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. And although systematic reviews are generally considered the highest tier of evidence, this particular review has been shown to contain so many major flaws and data errors that it should not be relied on for any public health decision.

And yet it remains one of the most cited pieces of evidence used to justify gender-affirming surgery—including for minors. It is perhaps the most influential zombie paper in gender medicine, being dragged around like Bernie Lomax in the movie Weekend at Bernie’s by activists, journalists, and supposed “experts” who need its corpse propped up to sell the illusion that it’s alive.

The central claim of the paper is simple: that among 7,928 transgender patients pooled across 27 studies, only 77—less than 1 percent—reported regret, and just 34 expressed what the authors categorized as “major” regret. They conclude that “there is an extremely low prevalence of regret in transgender patients after GAS.” This is the origin of the “1 percent regret” statistic for gender surgeries that has been repeated ad nauseam ever since.

But serious problems emerge the moment you look more closely. Shortly after publication, a Letter to the Editor by Pablo Expósito-Campos and Roberto D’Angelo appeared in the same journal, cataloging a list of serious concerns. The authors pointed out that numerous relevant studies fitting their search criteria had been omitted from the review. At the same time, the paper included studies that should have been omitted. More troubling still were the blatant data extraction errors, with sample sizes misreported, outcomes misrepresented, and methods misunderstood.

🎧 Prefer to listen?

Watch or listen to a full breakdown of this paper by evolutionary biologist Dr. Colin Wright and journalist Brad Polumbo on the latest episode of the Citation Needed podcast.

One of the most striking examples comes from the inclusion of a 1998 study by Kuiper et al. Bustos et al. claimed that the study followed 1,100 patients, of whom 10 regretted surgery. In reality, the study identified 10 regretful patients through a much narrower and more selective process: participants were recruited via newspaper and magazine advertisements, outreach to self-help groups for transsexuals, and invitations extended to patients of the Amsterdam gender team. Individuals then had to voluntarily agree to participate in an interview. The 1,100 figure cited by Bustos et al. refers not to the number of people surveyed, but to a rough estimate of the total number of gender surgeries that had taken place in the Netherlands up to that point. Claiming this as the sample size is an extreme misrepresentation.

Compounding the error, Bustos et al. claimed that the study recruited participants using “social media”—in 1998!

This is patently absurd. “Social media” did not exist at the time. MySpace, often credited as one of the first social media platforms, wasn’t launched until 2003. Twitter didn’t exist until 2006. For Bustos et al. to describe a 1998 recruitment method as using “social media” reflects a total lack of diligence. This is not a minor mistake. It is the kind of error that suggests the authors either misunderstood or did not carefully read the study they were citing.

Another massive error results from their handling of the 2018 study by Wiepjes et al., which contributed the largest share (over half!) of patients to their review.

Bustos reported that 4,863 individuals underwent surgery, when in fact the correct number was 2,627 (1,742 + 885 = 2,627).

The pattern repeats in their citation of a study on regret after vulvoplasty. The Bustos review claims that 80 people were assessed for regret, and only one regretted surgery. But the original study states that only 14 people were followed up by phone, with only one expressing regret. That alone is a 7 percent regret rate—not 1.25 percent. Worse, the regret was not about surgery itself but about having chosen vulvoplasty instead of vaginoplasty, which is a different question altogether.

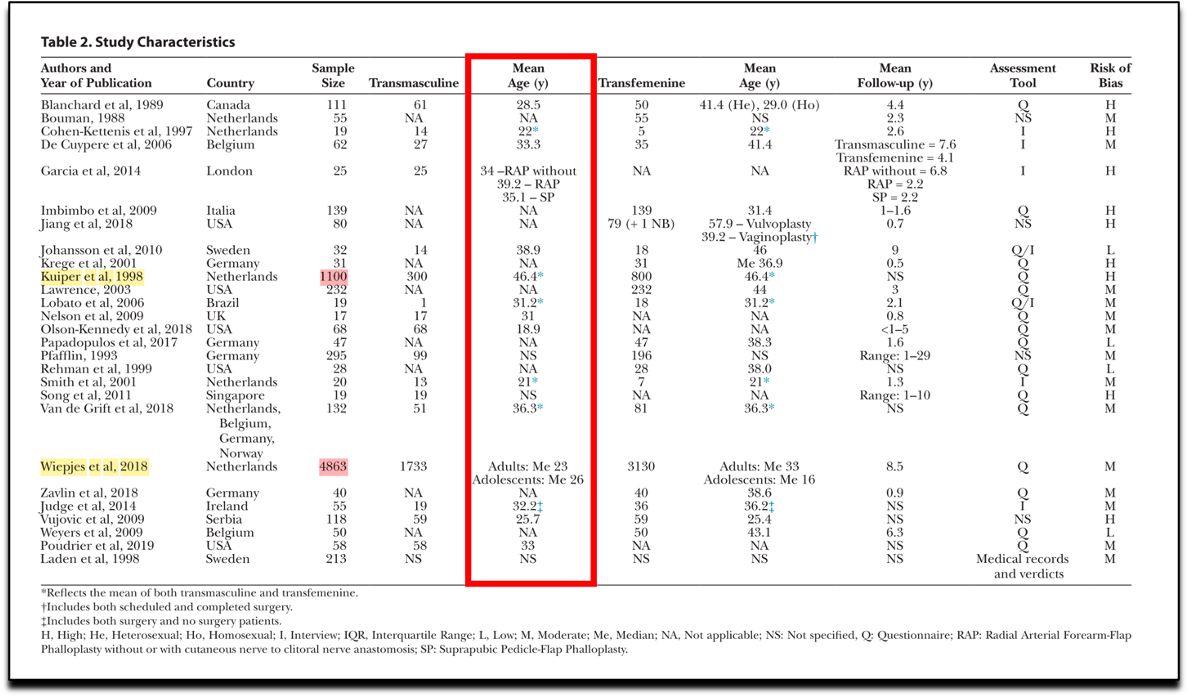

Independent analyst J.L. Cederblom conducted a forensic review of the Bustos review and documented dozens of additional errors. In Table 2 alone, Cederblom found nearly 50 mistakes: misreported sample sizes, missing data that were in fact specified in the original papers, and mislabeled authors and countries. Cederblom concluded that the errors extended into every column, touching 19 of the 27 included studies. “They don’t seem to have understood what they were reading,” he wrote.

But the paper’s problems go beyond data entry. Even if one were to correct every factual mistake, the study would still be fatally flawed in its design. Chief among the issues is the extremely short follow-up time in the majority of the studies included—often just one or two years. This is a serious limitation, as regret commonly takes much longer to emerge. According to multiple sources, the average and median time to regret after gender-affirming surgery is estimated to be between 8 and 8.5 years. Short-term studies simply cannot capture this delayed onset.

Moreover, many of the studies included in the Bustos review suffered from extraordinarily high loss to follow-up—some exceeding 40 percent! This should be a glaring red flag, since it stands to reason that the very individuals most likely to regret their surgeries might be the ones least likely to return to the same medical providers who facilitated their transition. Many detransitioners report feeling harmed, betrayed, or even traumatized by the gender medicine industry, and therefore want nothing more to do with it. As a result, they vanish from the follow-up pool entirely. Their absence from post-operative data does not mean they are happy—it means they’re gone. If anything, high attrition should lead researchers to assume that regret is being undercounted, not that it is rare.

Even the quality of the source studies was poor. Bustos et al. themselves acknowledge that 23 of the 27 studies were judged to have a moderate to high risk of bias. Very few had any control or comparison groups. And the populations studied were almost entirely composed of adults, with median ages in the 30s or older. Fewer than 1 percent of participants included in the review were minors when they received surgery.

When these problems were raised in the Letter to the Editor, the authors denied their errors. However, they then quietly issued an Erratum. They corrected the figure related to the 2018 study by Wiepjes et al., revising the sample size from the erroneously inflated 4,863 back down to the accurate count of 2,627. However, they left the egregious error in the 1998 Kuiper study untouched, still incorrectly reporting a sample size of 1,100 when in fact only 10 participants were interviewed. They also continued to include the vulvoplasty study that Bustos claimed assessed 80 people, even though the original study followed up with only 14.

In their written response to the Letter to the Editor, the authors of the Bustos paper did not engage with the substantive methodological critiques. Instead, they insisted that their search strategy had been “designed and conducted by an experienced librarian and the study’s principle investigator,” as if this alone validated their approach. They emphasized that their inclusion criteria and selection process were transparently documented in the methods section. But this was precisely the problem: the methods were flawed. Simply stating that you followed your own flawed protocol is more of a confession than a defense. Rather than defend their inclusion or exclusion criteria, the authors deflected, claiming that their process was rigorous by virtue of having followed a process. They ended their rebuttal with the assertion: “We strongly believe that this study is of very high-quality and adds important and relevant information to the literature.” Unbelievable.

In any other field of medicine—and science more generally—a paper with this many errors would be retracted, and its authors’ reputations would be forever tarnished. But in gender medicine, the usual rules of scientific rigor are routinely suspended. Criticism is unwelcome. Dissent is framed as political. Peer reviewers look the other way. And once a favorable statistic is published—however dubious—it becomes almost impossible to dislodge. The Bustos paper continues to be cited not because it is sound, but because it is useful.

So the next time you hear that “only 1 percent of people regret gender-affirming surgery,” remember where that number comes from. Remember the faulty assumptions, the miscounted participants, the omitted studies, the loss to follow-up, and the false generalizations.

The statistics in papers like this shape real-world policies that permit, and sometimes promote, irreversible interventions on children. They influence whether a 13-year-old girl undergoes a double mastectomy, or whether a teenage boy begins a drug regimen that will leave him sterile for life before he can fully grasp what that means. These are not theoretical harms. They are permanent, life-altering consequences that result from prioritizing ideology over truth.

The “1 percent regret” figure isn’t a scientific fact. It’s a myth built on a broken study—one that many have tried to correct, but that institutions still cling to because it serves their narrative.

Thank you for supporting Reality’s Last Stand! If you enjoyed this article and know someone else you think might enjoy it, please consider gifting a paid subscription below.

One of the serious issues is the "sunk cost" notion. Once you have your dick cut off, whatever you do, that dick is not coming back. If you show regret, you are basically saying "I really am a complete moron". So there is a lot of "brave-facing" going on. These persons are not going to admit that they screwed up their entire life.

I am glad you have highlighted that piece (the study). I do wonder if there ought to be a once a year coordinated effort amongst various influencers, commenters, activists, to highlight that piece (the study, and maybe highlight other studies in the same week) until they get retracted. Almost like an annual convention online. Today could be the start. At the start of every June, going forward, you could highlight this piece again, and if others in the community of caring about this issued joined you next year and further, it could rise in public awareness