Agustín Fuentes’ Book ‘Sex is a Spectrum’ Fails to Refute the Binary

Fuentes’ confused arguments against the sex binary ironically end up confirming it.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

Tomas Bogardus is a Professor of Philosophy at Pepperdine University. His academic papers on sex and gender can be found at his website, and he has a forthcoming book on the nature of the sexes, published by Routledge, available for pre-order. You can also follow him on X.com.

Princeton anthropologist Agustín Fuentes has recently written a book about the sexes. That much is clear. What exactly he means to say about the sexes, however, is significantly less clear. On the cover of the book, we find this title and subtitle: Sex is a Spectrum: The Biological Limits of the Binary. So, evidently, “the binary” has limits. We get a further clue as to the thesis of this book when we read the title of the seventh chapter: “Why the Binary View is a Problem.” So, it seems as though Fuentes takes issue with “the binary view.” This is further confirmed by the last line of the book (p. 150), which says, “…there is need to move past the sex and gender binary. Let’s do everything we can to make that happen.” And, finally, on the back cover, we’re told the book will explain “Why human biology is far more expansive than the simple categories of female and male.”

So, from front to back this book wants to say that “the binary view” is false. Or, at least, that the binary view is problematic in some way. But what exactly is “the binary view”? Below, I will survey some options suggested by the text, and evaluate them in turn.

What is ‘the Binary View’?

It’s clear that Fuentes means to target “the binary view.” But it’s unclear what the binary view is meant to be. The first possibility is suggested by the back cover, which says the book explains “why we can acknowledge that females and males are not the same while also embracing a biocultural reality where none of us fits neatly into only one of two categories.” So, perhaps this is what Fuentes means by “the binary view”:

Binary View 1.0: Some of us are clearly only male, or clearly only female.

Perhaps Fuentes means to deny this, and to claim that none of us is clearly male, or clearly female. But if Binary View 1.0 is what Fuentes means by “the binary view,” it seems hopeless to argue against it. For surely Binary View v.1.0 is true. I myself am clearly only male, for example. And so are at least some of the wild peacocks that roam my neighborhood. No doubt it’s true that many (all?) of our biological concepts admit of borderline cases. Nevertheless, at least some also admit of clear cases. “Male” and “female” are two examples.

What Fuentes seems to be trying to express is that while some of us are male and others of us are female, nobody is “neatly” one or the other. Because, as he says on page 36, “bodies, physiology, and behavior are not so easily classified, and are queer indeed.” In other words, while I might be clearly only male, nevertheless, Fuentes thinks, at least some of my sex biology—some of my sex-linked traits—will be had by at least some females. This brings us to the second possible meaning of “the binary view.”

The second possible interpretation of “the binary view” is hinted at on page 2 of the text, where Fuentes says, “this spectrum of variation tells us that females and males are not two different kinds of thing.” He expands on this on page 4:

…biology as it relates to sex is not binary, meaning that it does not come in two distinct kinds: male and female. This is not to say that females and males are the same. They aren’t. …It’s just that not all humans fit neatly into the categories of female or male, and biological measures of human bodies rarely segregate into two non-overlapping categories. Neither ‘female’ nor ‘male’ describes a uniform or distinct biological type.

On page 123 we return to this theme: “Given everything we’ve covered so far, it’s clear that the human ‘sexes’ are not just biology or just culture, they are not ‘the same’, but nor are they ‘different kinds’.” And on page 149, in a section titled “The Binary is Wrong and Harmful,” Fuentes says this: “There are few simple one-to-one universal ‘truths’ about being a female or male, and treating those two categories as different kinds of being is not supported by the science of sex biology.”

On the face of it, these quotations are paradoxical. Females and males are not different kinds of things, and yet neither are they the same (kind of thing?). But notice that quotation from page 4 restricts our attention to “biology as it relates to sex.” And that’s largely what this book is about. On page 77, Fuentes says: “In this book, we are interested in the actual variation in and the patterns of sex biology.”

What are we to make of these quotations? Being charitable to an anthropologist not trained in philosophical clarity or precision, these quotations suggest the following interpretation of “the binary view”:

Binary View 2.0: Sex-linked traits are never shared among both females and males.

On the contrary, Fuentes thinks: sex-linked traits are often shared among both females and males. Females and males are indeed different, but they are not “very different” (cf. p. 111), where being very different entails that their sex-linked traits are never shared, and never overlap. This interpretation helps explain why Fuentes spends so very much time describing variation of sex-linked traits across the plant and animal kingdoms.

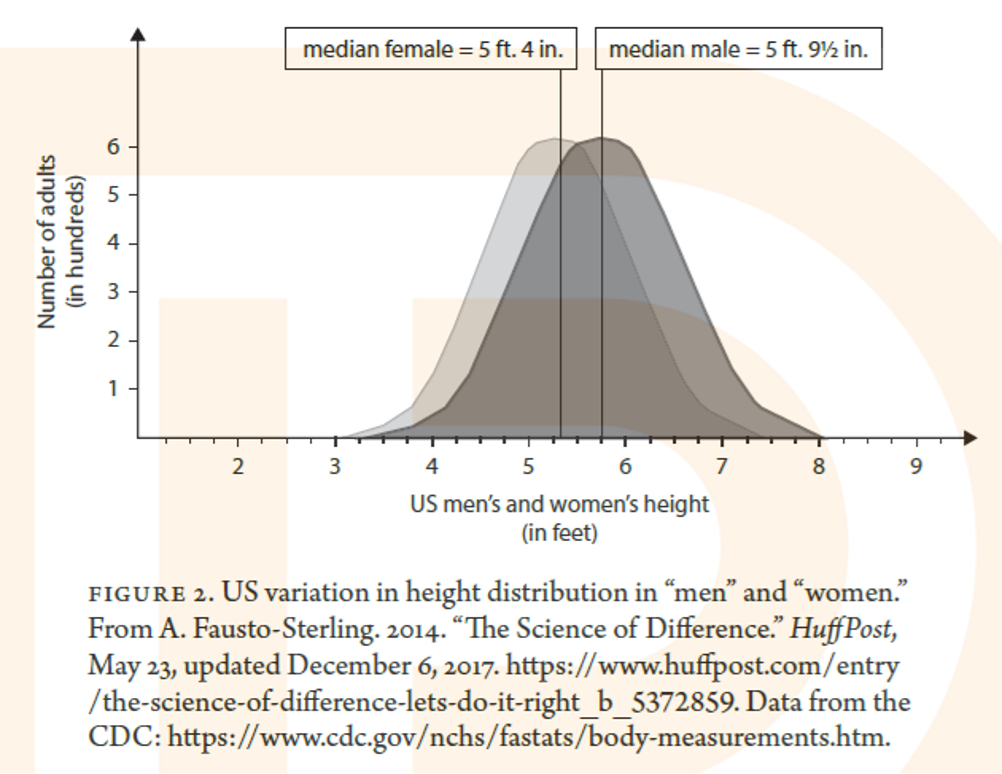

By way of response, yes, Binary View 2.0 is no doubt false. But who would say otherwise? Some males and females are the same height, the same weight, have the same hormone levels, have similar patterns of body hair, etc. For at least some sex-linked traits, plotting the distributions of males and females would result in a bimodal distribution, as we see in Fuentes’ Figure 2 on page 75:

On that page (p. 75), Fuentes says this: “The majority of human sex biology works in the same way as height does: it is morphology with a range of expression across human bodies.” Yes. Indeed. That is how much of human sex biology works.

But, of course, graphs like this presuppose that there are males and females, and that these are different groups, different kinds. The distribution of heights for males is graphed alongside the distribution of heights for females. Recall that Fuentes claims that the sexes are not different, but neither are they the same. I believe this is the best sense that can be made of that claim: The sexes are not different, i.e. many of their sex-linked traits are shared. Yet neither are they the same, since males and females both exist, and are distinct kinds.

But, to repeat: Who would disagree? If the thesis of Fuentes’ book is that Binary View 2.0 is false, he really ought to have supplied at least one citation of someone saying that it’s true. But he doesn’t do that. So, unfortunately, if this is what the book is about, it seems to be one long exercise in shadowboxing, one long adventure in tilting at windmills. Fuentes is battling opponents who do not exist.

There’s a third possible interpretation of “the binary view,” which would certainly put this book into conversation with people who disagree. Recall that the back cover also says the book is about “Why human biology is far more expansive than the simple categories of female and male.” Perhaps we’re meant to read this spatial metaphor—“more expansive”—as challenging the following view:

Binary View 3.0: There are exactly two sexes: male and female.

If Fuentes thinks Binary View 3.0 is false, that would indeed be worth saying, and worth arguing for. That would engage some of the recent discussion in the literature as well as the popular culture. And this interpretation is supported by parts of the text, as we’ll see below. In the book, Fuentes seems to give reasons to think there might be more than two sexes, reasons having to do with mating types, reasons having to do with some birds, and reasons having to do with disorders of sexual development.

Let’s discuss these arguments in turn.

The Argument from Mating Types

Let’s think about the first argument Fuentes seems to give in favor of thinking that there are more than two sexes. On page 6, Fuentes says this: “Even in their earliest appearances, the number of mating types (often called ‘sexes’) per kind of species has been variable, ranging from two and sometimes three in most animals, to as many as seven in single-celled organisms, thirteen in slime molds, and thousands in some fungi.” So, the idea seems to be that so-called “mating types” are themselves sexes, and there are very many mating types in nature, so there are very many sexes in nature. Far more than two.

However, mating types are not types of sexes.

As biologists use the words “sex” and “sexes,” these seem to be reserved for species that reproduce using gametes that are different in the right kind of way, i.e. species that are anisogamous. The relevant differences often cited are size, motility, number, direction of gene flow, and the like. This is in contrast to species that reproduce sexually, but by using gametes that are the same in these ways, i.e. species that are isogamous. In many isogamous species, though the gametes are roughly the same when it comes to size, motility, number, etc., nevertheless some are incompatible with others. And, so, these species are said to involve “mating types.”

I admit it’s possible that, when confronted with isogamous sexually reproducing organisms, biologists could have decided to track the more general functions to produce any gamete type with the use of ‘sex’, and as a result truly say there are many sexes. But evidently they haven’t done that. I think that Lachance et al. (2024, 1) are correct when they diagnose the situation this way: “the supposition that some fungi feature thousands of sexes…, that a cellular slime mould has three sexes…, or that Tetrahymena thermophila is a seven-sex species…, is in every case a patent misuse of ‘sexes’ as a synonym of mating types, perhaps motivated by the wish to enhance the allure of journal article titles.”

A survey of the literature on sexual reproduction reveals, I believe, that biologists have decided not to use “sex” to refer to the more general function of producing any gamete type—isogamous or anisogamous—but instead to refer to the more specific function of producing anisogamous gamete types.

Consider this analogy: “curveball,” as the word is used in baseball, could have referred to any pitch that curves. Indeed, to the uninitiated, that’s exactly how it sounds. But, actually, it refers to a more specific type of pitch, with a particular kind of curve. There are other pitches that literally curve but which are not curveballs, for example sliders, sinkers, sweepers, and screwballs. Similarly, “mating types” does sound like it ought to include the sexes. After all, aren’t males and females types that mate? Evidently, though, biologists seem to reserve the word “sexes” for anisogamous species, and they use “mating types” for isogamous species.

Consider David Nanney (1980, 49), for example, who puts it this way: “The term mating type is preferable to sexes, because sexes suggests a differentiation of gametic function that is inapplicable in conjugation.” So, Fuentes’ first argument for the conclusion that there are more than two sexes doesn’t work, relying as it does on the false premise that mating types are sexes.

Let’s turn, then, to his second argument.

The Argument from Sparrows

On pages 30 to 31, Fuentes reasons this way:

Like so many other animals, the patterns of how sex biology varies with bird species is dynamic and multifactorial: there are not simply two uniform sex types…. There are even some bird species with multiple ‘sex’ categories. The white-throated sparrow has some changes to its chromosomes that effectively produce four chromosomal types that have different plumages and a mating system wherein certain types are not compatible with others. So, while there are only two gamete-producing physiologies in the species, there are functionally four sexes in the reality of the actual mating system.

The idea seems to be that this species of sparrow features multiple sex categories, indeed that there are “functionally four sexes” in this species. And the reason is that, allegedly, males with a certain plumage are not reproductively compatible with females of a certain plumage.

However, the reality of the situation is less exciting than Fuentes’ click-bait headline. The white-striped and tan-striped varieties of this sparrow are reproductively compatible, it’s just that cross-type pairs are far more common, as they do better as breeding pairs. White-striped males and females are more aggressive. Tan-striped males and females feed young more often than white-striped birds. When it comes to having and raising young, the behaviors seem to complement each other, which is why we tend to see more cross-type breeding pairs. But not always.

Thomas et al. (2008, 1456) put the situation this way: there is “a strong disassortative mating preference (Lowther 1961) such that 96% of observed breeding pairs are composed of birds from both morphs.” They say also that there is a “low frequency (~2.5%) of WS x WS breeding pairs.” So, Fuentes is incorrect to say that males of one type are reproductively incompatible with females of another type. These types rarely mate, but that doesn't mean they cannot mate, as Fuentes says. And, crucially for our purposes, despite all this, there are still only two sexes in this species. Thomas et al. (ibid., 1456) again: “WS males and females thus exhibit behavior that is more male like than their sex-matched TS counterparts.” Note that white-striped males and females have sex-matched counterparts among the tan-striped birds. Maney and Goodson (2011, §IV.A) agree: “Both males and females can be categorized into one of two plumage morphs that differ primarily in the color of the crown stripes.”

The two plumage morphs both contain males and females. There are no third or fourth sexes in this species.

The fact is that WS x TS breeding pairs are much more common than WS x WS or TS x TS breeding pairs. And yet, nevertheless, WS males and TS males are both males; they are not distinct sexes, nor even “functionally” distinct sexes, as Fuentes puts it. And similarly for the females.

An analogy can help us see why Fuentes’ argument is invalid here: Intra-nation, intra-race, and intra-religion breeding pairs are far more common than inter-nation, inter-race, and inter-religion breeding pairs. Consider the higher frequency of Muslim-Muslim and Hindu-Hindu pairings, for example, than Muslim-Hindu pairings. And yet Muslim males and Hindu males are both males, and Muslim females and Hindu females are both females. It’s hardly the case that there are (“functionally”) multiple sexes among Muslims and Hindus. I conclude, then, that this second argument from Fuentes is as unsuccessful as the first.

We’ll turn, then, to Fuentes’ third and final argument against Binary View 3.0, i.e. in favor of the claim that there are more than two sexes.

The Argument from Disorders of Sexual Development

On page 46, Fuentes tells us that “sex at birth” is hoping to measure the 3G category of sex. He explains: “The three Gs are genes, gonads, and genitals. A ‘3G female’ is a human who has XX twenty-third chromosomes, ovaries, and a clitoris/vagina/ labia.”

Later, on page 141, Fuentes seems to argue that there are more than two sexes, using the case of Olympic athlete Caster Semenya:

Ms. Semenya has higher-circulating testosterone than is typical for 3G females, a Y chromosome, and internal gonads that are the equivalent of undescended testes. Ms. Semenya is a woman whose sex biology is outside what is typical for 3G females but well within the range of variation found in our species. The binary view, however, does not allow space for her.

Fuentes seems to be reasoning this way:

If Semenya is a woman whose sex biology is outside what is typical for 3G females, then the binary view “does not allow space for her.”

If the binary view does not allow space for Semenya, then Semenya is neither male nor female, but a third sex.

Semenya is a woman whose biology is outside what is typical for 3G females.

Therefore, Semenya is neither male nor female, but a third sex.

Therefore, there are at least three sexes.

In response, the sober fact of the matter is that Caster Semenya is a male, as evidenced by the presence of a Y chromosome and internal testes. Since women are adult human females and men are adult human males, it follows that Semenya is not a woman, but rather is a man. (Whether it is failure of courtesy to say so, and what our public policy should be with regard to individuals with disorders of sexual development, are further questions.) So, premise 3 is false.

But even if Semenya were a woman, presumably, in that case, she would also be female. And, in that case, it’s hard to see how premise 1 could be true. Why think that the binary view of sex would not allow space for Semenya? If Semenya were female, then it seems as though the binary view of sex accommodates this case rather straightforwardly. Similarly if Semenya is male. If Fuentes really thinks that Semenya is a third sex, one wonders what a sex is, on Fuentes’ view, such that there could be three of them.

In the following section, we will turn to that question: What is a sex, according to Fuentes?

But does Fuentes really think that there are more than two sexes? On the one hand, it seems like he does. Recall that Fuentes says that mating types are often called “sexes,” and there are thousands of mating types. He says that there are some bird species with multiple “sex” categories. And he says that the binary view of sex “does not allow space” for people like Caster Semenya. Together, this seems to me like powerful evidence that Fuentes means to argue that there are more than two sexes. Sarah Richardson (2025, 437), in a recent review of Fuentes’ book, reads him as saying that “there are not only two sexes, and sex can most definitely change.” So, there’s at least one prominent ideological ally who hears Fuentes talk out of that side of his mouth.

But, out of the other side of his mouth, he tells a very different story. On the podcast Academics Write, published on June 19th, 2025, at the 9:25 mark, Fuentes says this about his book: “And so I’m not saying there’s [sic] more than two sexes—there are male and female, that’s how we’re talking about it. But male and female are not essential, distinct entities compared to one another. They’re typical clusters of variation. And within each of those typical clusters, there’s huge variation.”

What are we to conclude from all this?

Unfortunately, it seems me the best explanation is that Fuentes’ view is not clear even to himself, and that he vacillates between a controversial and implausible claim that there are more than two sexes, and the modest and uncontroversial claims that sex-linked traits are often shared among both females and males, and that sex-linked traits vary significantly among males and among females. That is, Fuentes conflates an interesting but false thesis with a trivially true thesis, retreating to the latter when the former is challenged. A motte and a bailey, one might say.

What is a Sex?

Let us turn now to the question of what a sex is, according to Fuentes. In this book, he seems to endorse a gamete-based account of males and females. On page 1, we read this:

“Imagine you are a fish called a bluehead wrasse… You are what we’d call female, so you produce eggs. There is only one very large member of your group, and they are the group male, so produce sperm.”

And on page 29 he moves seamlessly between these two descriptions:

“There are species [of reptiles] where females are larger than males…, others where males are larger than females…, and yet others where there is little or no size difference… …it’s likely that both competition between small-gamete producers… and environmental constraints on body size (for both small- and large-gamete producers) are involved.”

This happens again on pages 33-4:

“Similarly, there is a whole group of primates that challenges the expected roles of large- and small-gamete producers. Most primates live in big groups of several males and females and young, and others live in groups of one male and many females and young….”

So, it sure looks as though Fuentes admits that the sexes are defined in terms of gamete production: females are “large-gamete producers,” and males are “small-gamete producers.” One might think, then, that Fuentes would define having a sex more generally as the producing an anisogamous gamete-type (sperm or eggs).

And yet he does not do that.

When it comes to what sex is, Fuentes says this on page 39: “Biologically, ‘sex’ [sic] involves all the processes of sexual reproduction—not just gametes.” I notice that the Random House Dictionary offers a similar definition of “sex”:

3. the sum of the structural and functional differences by which male, female, and sometimes intersex organisms are distinguished, or the phenomena or behavior dependent on these differences: These plants change sex depending on how much light they receive.

However, it cannot literally be true that sex “involves” all the process of sexual reproduction, since many organisms have a sex without having all the processes of sexual reproduction, or even any processes of sexual reproduction. Embryos, for example. Or an organism that has been severely injured. Sex cannot be the sum that the Random House Dictionary refers to, since many organisms have a sex without having that sum. To put it another way, “sex” can’t mean all sex biology, or even all of a particular organism’s sex biology. First of all, this definition of circular, using “sex” in the definition of sex. What’s more, on this definition puberty would be a change of an organism’s sex, since it’s a change of an organism’s sex biology.

On page 40, Fuentes expresses what is now a common line about sex, namely that it is very complex: “What is referred to as ‘sex’ biologically comprises multiple traits and processes with variable distributions and patterns.” I believe here he means to endorse the claim that “sex” is ambiguous, or perhaps semantically indeterminate: there is no “sex itself” (see for example Richardson 2022, 10), but rather only “types” (Fausto-Sterling 2016, 198) or “variables” (Money et al. 1955, 302) of sex, for example chromosomal sex, hormonal sex, phenotypic sex, perhaps brain sex, and so on and so on.

But there are strong reasons to deny that sex “comprises” multiple traits and processes. There is really only one trait that seems to be necessary and sufficient for being a male, namely having the function of producing a component with the function of producing sperm. And similarly for females, with regard to ova. To be “hormonally female” is to have hormone levels typical of the females of the species, but a male who has e.g. hormone levels typical of females of that species does not literally become a female in any sense of the word. Nor does he have multiple sexes, being both male and female.

Instead, what’s true is that there are many traits and processes that are linked to sex—there are a variety of sex-linked traits. But in order for these traits to be linked to sex, they must be distinct from sex. Fuentes is mistaken, then, to think that sex “comprises” multiple traits and processes: he’s confusing a multiplicity of sex-linked traits with sex itself.

On page 140, Fuentes gestures approvingly toward so-called sex contextualism (cf. Richardson 2022):

“Drawing on the conceptual framework of ‘sex contextualism’ can be particular useful when it comes to medicine and biomedical research. This view emphasizes that ‘male’ and ‘female’ or ‘men’ and ‘women’ do not mean the same things in all contexts, nor are these the only subclasses or categories that are applicable or useful in biomedical research… Sex contextualism… recognizes the pluralism and context-specificity of operationalizations of ‘sex’ across medical research and urges practitioners to attend to, be clear about, and be consistent with the uses and meanings of the classification used in the design, interpretation, and communication of that research.”

But this, too, is mistaken.

The fact that sex might be operationalized differently in different research contexts does not mean that “sex” is ambiguous, or semantically indeterminate, or context-sensitive. Compare: Dr. Smith and Dr. Jones might operationalize job satisfaction in different ways for different studies: maybe Smith looks at survey results, and Jones looks at retention rates. But in order for these studies to be about the same thing, “job satisfaction” must have some shared sense across studies. The fact that job satisfaction is operationalized differently in these studies does not mean that they’re not both studies about job satisfaction. Similarly, Dr. Smith and Dr. Jones might operationalize sex in different ways for different studies. But in order for these studies to be about the same thing, “sex” must have some shared sense.

One last mistake. Let’s circle back to page 46, where Fuentes says this:

“What ‘sex at birth’ is hoping to measure is really what is called the 3G category of sex. The three Gs are genes, gonads, and genitals. A ‘3G female’ is a human who has XX twenty-third chromosomes, ovaries, and a clitoris/vagina/labia. A ‘3G male’ is a human who is XY and has testes and a penis/scrotum.”

In response, no, this is not what “sex” or “sex at birth” refers to. Embryos can have a sex, without being 3G male or 3G female. Due to accident, injury, surgery, etc., a male may not be 3G, or a female not 3G, even at birth. There are males and females in other species that are not 3G, even at birth. Crocodiles are male or female, but never 3G, since they don’t have sex chromosomes. So, being a 3G female is different from being a female. Being a 3G male is different from being male. Fuentes is mistaken.

What “sex at birth” refers to is sex, at birth. And sex, at birth or at any other time, is not equivalent to the 3G category of sex. These three G’s may be useful ways in which we come to know what a person’s sex is. But checking someone’s drivers license is also a good way to know what a person’s sex is. Nobody would mistake what a drivers license says for sex itself, and in the same way we should not confuse these three G’s for sex itself.

A Fuentes-inspired Argument that Sex is Binary

As we saw above, Fuentes seems concerned first and foremost with showing that “the binary view” is a problem. Though we’ve seen that it’s not at all clear what “the binary view” amounts to, I think it’s worth pointing out that Fuentes himself provides the reader with the premises required to construct an argument for the conclusion that sex is, indeed, binary. Let me explain.

On page 36 we find this: “Gametes (sperm and ova) in most mammals can be described as binary, one large and one small. But bodies, physiology, and behavior are not so easily classified, and are queer indeed.” Earlier, on page 11, Fuentes says something similar: “While the gametes themselves mostly come in two types (a binary), most of the rest of the biology in organisms does not.”

In describing gametes as binary, Fuentes seems to be reasoning this way:

If a system consists of two types, then it is aptly described as binary.

The system of gametes in mammals consists of two types.

So, the system of gametes in mammals is aptly described as binary.

In defense of premise 1, one might consider binary star systems and binary code. A similar principle would explain why DNA is described as a quaternary code (e.g. Zhang et al. 2019, 2).

The problem for Fuentes is: if this system of gametes can be described as binary, why can’t the system of organs that produce them? And if sexes are defined in terms of those organs, why can’t the sexes be described as binary? That is, why can’t we use Fuentes’ premise (1), together with a premise like this:

2*. The system of biological functions to produce anisogamous gametes

consists of two types: the function of producing sperm, and the function of

producing ova.And a premise like this:

3*. The sexes are biological functions to produce anisogamous gametes. Males

are organisms with the biological function of producing sperm; females, ova.To get this conclusion:

4. Therefore, the system of sexes is aptly described as binary.

If “the binary view is a problem,” as Chapter 7 tells us, well, then, Agustín, we have a problem.

Though Fuentes offers much sound and fury against “the binary view,” in the end it amounts to nothing: his thesis is either uncontroversially true or obviously false. Even worse, in tragic Shakespearean fashion, Fuentes sows the seeds of his own undoing, unwittingly supplying himself with premises sufficient to prove that the title of his book is exactly false: Sex itself is not a spectrum at all, but rather is binary.

If you enjoyed this free article, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below to show your support. Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication, and your help is greatly appreciated.

A car missing a couple of wheels is still a car, but defective. It hasn't transed itself into a bicycle!

A person with DSD is still male or female, but with a malfunction.

Even little kids know this stuff.

In a world that is burning, for the sake of profits, where tyrants thrive, wars rage & peoples starve, opinion replaces truth - how could Fuentes think this book was a good use of his time - or ours?

This is The Age Of The Death Of Reason...

Can the great philosopher explain why, in spite of sex *not* being binary, every human since the beginning of time has exactly two parents?

That bold statement doesn't sell books, I guess.