How Our Shoes Can Help Explain the Biology of Sex

There are no good reasons to doubt that sex is, in fact, binary.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

What is sex?

When asked questions like “What is a male?” or “What is a female?” many people immediately think of our own species, of human males and human females. And so you’ll often hear answers that pick out features having to do with our chromosomes, or our genitalia, or our hormone levels, or the typical expectations of and social roles played by human males and human females: “Males? Oh, a male has XY chromosomes, male genitals, chest hair, and he’s drawn to sports, Coors Light, violence, etc.” But which if any of these answers is the right answer?

Some people think all of those answers are equally valid. In fact, it’s fashionable these days in many circles to insist that the word “sex” is ambiguous, and that a more up-to-date and nuanced understanding of sex would distinguish among an ever-increasing list of types of sex: chromosomal sex, anatomical/phenotypic sex, hormonal sex, gonadal sex, genital sex, perhaps cellular sex, brain sex, sexual identity, social sex, and so on. And, they’ll say, most if not all of these describe quantities or characteristics that can vary in degree, and so can be charted along some axis. “Sex is a spectrum,” we’re told commanded.

But this is a mistake. The easiest way to see this requires freeing ourselves from this chauvinism about our own species. It’s well documented that other species reproduce sexually, and that there are males and females in other species. In fact, sexual reproduction is a very old evolutionary strategy, which far predates the existence of the North Star (70 million years old), the rings of Saturn (10 to 100 million years old), and even trees (approximately 370 million years old). Primitive forms of sexual reproduction date back about two billion years, but complex organisms like sharks have been using this strategy for at least 450 million years. If there’s anything new under the sun, it’s certainly not sex.

Take organisms in the humble phylum Placozoa, for example, whose bodies consist of just a few thousand cells, of only four types. Yet these primitive organisms can be described as featuring males and females, despite sharing none of those alleged types of sex mentioned a moment ago. These organisms reproduce sexually, but in a very different way from us when it comes to chromosomes, genitalia, hormones, social roles, and the like.

So, there have long been species that have everything that’s required to include males and females, and yet which are very different from humans, some being very primitive. So, whatever makes an organism male or female must be very simple, and must have been around for a long time.

What could that be? Simply this: males produce sperm, females produce ova. That’s all that Placozoa do to count as male or female, so that must be all that’s required to be male or female. In non-political contexts, biologists agree. Describing the bluehead wrasse, a species of fish that can change sex under certain environmental conditions, Campbell’s 9th edition of Biology says this (p. 999): “a female wrasse undergoes sex reversal, a change in sex. Within a week, the transformed individual is producing sperm instead of eggs.”

So, males produce sperm and females produce eggs. But, there’s an important caveat here. Biologists often use this sort of present-tense construction to describe what things do—hearts pump blood; kidneys filter waste; the CCR5 receptor binds to chemokines—but of course they acknowledge that, due to disease, injury, mutation, etc., a heart may not pump blood, and kidneys may not filter waste, and the CCR5 receptor may not bind chemokines.

So, biologists seem to be describing function. The function of a heart is to pump blood. But it may malfunction, due to heart disease, or injury, etc. Males produce sperm; that is the function that makes an organism a male. But that function may not be fulfilled, due to immaturity, disease, injury, etc. In this way, being male is just like every other functional concept in biology—of which there are many. So, males who don’t actually produce sperm and females who don’t actually produce eggs are no more of an objection to this biological concept than are kidneys that don’t actually filter waste or CCR5 receptors that don’t actually bind chemokines.

The bottom line is this: a male is an organism with the function of producing sperm. That is, when the organism is functioning properly—when it is flourishing, fully mature, uninjured, healthy, and so on—this organism will produce sperm. If there’s no disorder, no interference, no malfunction, that’s what will happen. That’s the plan, so to speak. And similarly for females, with regard to ova. That’s all it is to be male or to be female. Simple.

The alleged types of sex I mentioned above are not, actually, types of sex. They are, as John Money (boo, hiss) called them in the 1950s, “variables of sex.” Harry Benjamin called them “kinds of sex” in the 1960s, and others call them “markers of sex.” So-called “chromosomal sex” is the chromosomal structure typical of the males or of females of the species. Social sex is the social role typical of males or of females of the species. And so on, for the other markers of sex. But a marker of sex is one thing, and sex is something else. (Just as typical markers of gold—being yellow, lustrous, soft, etc.—are different from gold itself, the element that typically appears yellow, lustrous, etc.)

You can see that by noticing the italicized appearances of “male” and “female” in the definitions of all these markers of sex: those are the true, fundamental notions of biological sex. And they are defined in the way explained above, in terms of having the function of producing either sperm or ova. A “chromosomal male” is, in humans, someone with XY chromosomes, because that is the chromosomal arrangement typical of human males, i.e. humans who have the function of producing sperm.

How many sexes are there?

There are two sexes, because the sexes are defined in terms of gametes, and—in anisogamous species like ours—there are two types of gametes, sperm and eggs. But another interesting question is, how many sexes could there be? The answer to that question depends on how many types of gametes there could be.

As a matter of fact, here in reality, evolution has selected for a strategy of sexual reproduction that relies on getting two gamete-types together, each carrying half a genome, in order to produce a new organism with a complete genome. But it’s in principle possible for a species to evolve with a strategy of sexual reproduction that relies on getting three or more types of gametes together—a Captain Planet sort of situation, for my fellow ‘80s kids out there (“With your powers combined…”). It’s difficult to see how this would be an adaptive strategy, though. It’s hard enough to get a duet together, let alone an orchestra. But it’s at least possible that there be more than two sexes.1

Yet this is merely an intriguing theoretical possibility. The way things have actually gone, the way reality actually is, there are only two types of gametes. And, therefore, only two sexes.

How many sexes can something be?

So, when it comes to sexes, there are only two options: male or female. But it’s possible that an organism be both male and female. Indeed, if you reflect on what it means to be male—having the function of producing sperm—and what it means to be female—having the function of producing ova—you’ll realize that there’s nothing in these definitions that rules out an organism having both functions, and therefore being both male and female. An organism could have the function of producing sperm and also the function of producing ova, just as an ordinary hammer can have two functions, both to drive and to extract nails.

In fact, there are organisms that do this regularly, i.e. organisms that are true simultaneous hermaphrodites. The common garden snail, for example, is a simultaneous hermaphrodite. Each snail contains within itself the capacity to produce both sperm and eggs. Each snail is, therefore, both male and female.

There are, to my knowledge, no clear cases of true simultaneous hermaphrodites in humans. Perhaps the best candidate case is this one, from the 1970s. But my understanding is this patient’s condition was the result of mosaicism: the patient’s body consisted of cells with different genomes, most XY but some XX. Due to the relatively small proportion of the patient’s body that bore XX chromosomes—and, as a result, produced ovarian tissue—probably the right way to characterize this case is as that of a male who carried within himself a small amount of foreign, female tissue. If that’s right, then this would not be a case of a true hermaphrodite. But, for our purposes, the point right now is just that true hermaphrodites are theoretically, philosophically, hypothetically possible. And, indeed, in other species, actual.

We must also point out that many organisms do not reproduce sexually at all, and therefore do not feature males and females as sub-types of the species. And some species reproduce sexually, but via “isogamy,” i.e. gametes of the same size, neither sperm nor eggs. In these species, organisms are neither male nor female. While it’s very controversial whether any human has lacked both the function of producing sperm and also the function of producing eggs, we should again acknowledge that it is theoretically possible. (And, recall, failing to fulfill a function is not the same as lacking the function. Of course, many humans fail to produce gametes at all, due to age, injury, disease, and so on. What's controversial is the claim that there’s ever been a human who wasn’t naturally disposed to produce gametes, when functioning properly.)

So, that exhausts the possibilities. Some individual organisms are only male. Some are only female. Some are both male and female. And some are neither male nor female. But these facts have led some to claim that sex is not a binary variable. They claim, that is, that what sex a person is, is not a binary variable. For example, I recently had a friendly conversation with Dr. Avi Bitterman on his YouTube channel, where we discussed this very question (feel free to skip ahead to this point in the conversation, if you’re interested). Dr. Bitterman’s position is that sex is not a binary variable, i.e. the sex a person is, is not a binary variable. But let me explain why this way of putting things may mislead some people into a mistaken understanding of biological sex.

Is the sex people are a binary variable? The Shoe Analogy

Strictly speaking, sex is not a variable at all. Variables are bits of syntax in a formal language—characters like “x” and “y”—while sex is, as we’ve seen, the function of producing sperm or ova, and this function is a feature had by organisms out there in the world, not in a formal language. But I take the question to be asking whether, were we to model biological sex in some formal language, in some theoretical description of reality, would the variable we use to model an organism’s sex be binary, or not?

I believe the answer is clearer than the question. When it comes to how many sexes there are, Dr. Bitterman agrees: there are only two, male and female. But when it comes to what’s going on with any given organism when it comes to biological sex, there are four possibilities: the organism is only male, or only female, or both male and female, or neither male nor female. But what’s going on in an organism with regard to sex is not itself biological sex. Indeed, as you can see with the boldfaced instance of “sex” in the previous sentence, the former is defined in terms of the latter. These combinations of sex are not themselves sexes. You can see this especially clearly by focusing on the last combination: neither male nor female. Clearly, being neither male nor female is not itself a biological sex. It’s not the function of producing a certain type of gamete; it’s the lack of any such function.

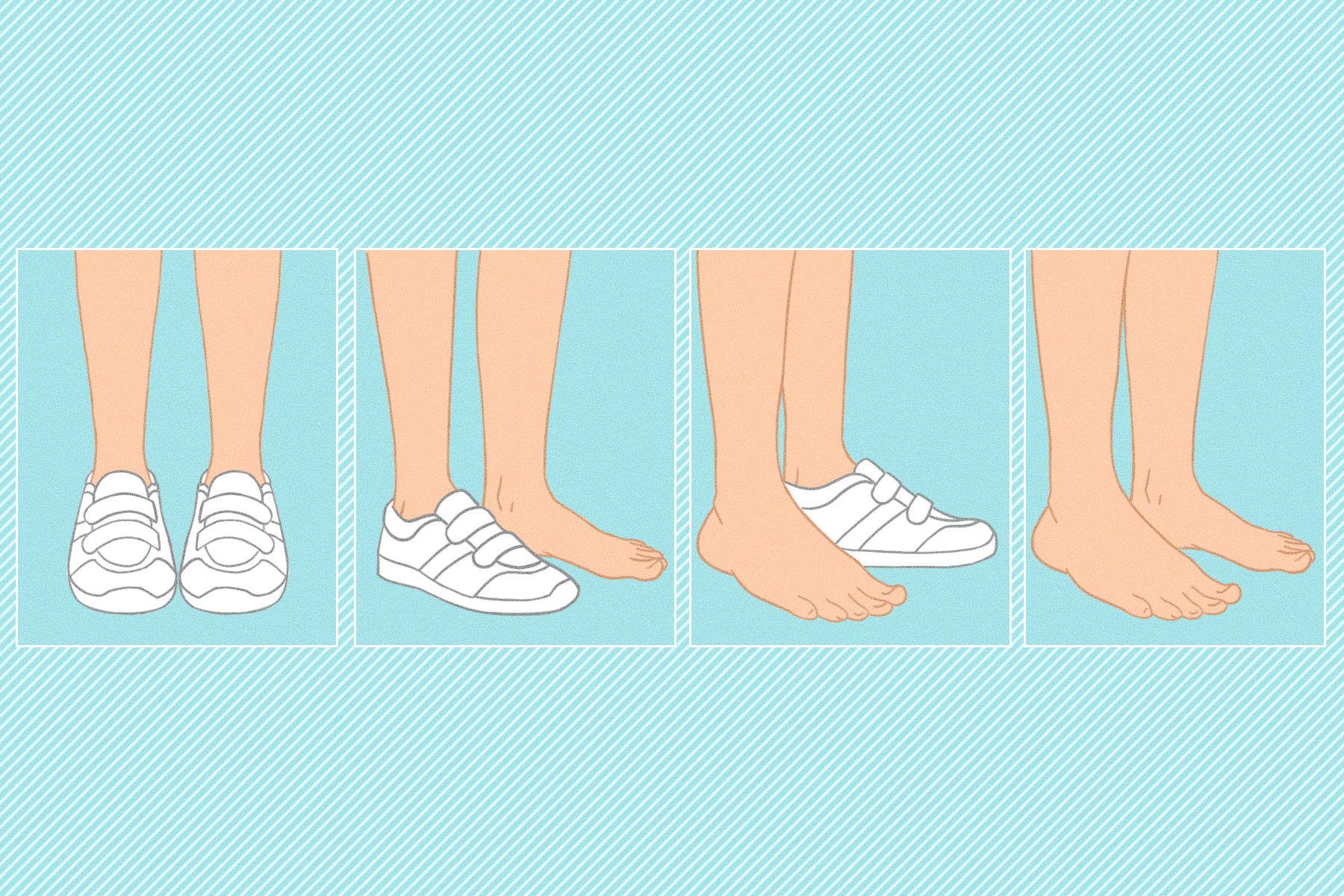

It’s a bit like shoes. Just as there are, in reality, only two sexes, there are, in reality only two types of shoes out there for people: left-footed shoes and right-footed shoes. And yet there are four ways that a person can be “shoed,” so to speak. A person can wear a right shoe only, or a left shoe only, or both right and left shoes, or no shoes at all. And so, just as we can think of “the sex a person is,” or, in other words, what’s going on in a person with regard to sex, we can also think about “the shoes a person wears,” or what’s going on with a person when it comes to shoes. And, in both cases, there are four possibilities, four combinations. But, as before, it would be a mistake to think of these combinations of shoes as themselves shoes. Clearly, wearing no shoes at all is not a type of shoe. In the shoe system, there are only two kinds of shoes. The system is binary, in that way. Similarly, in the sex system, there are only two kinds of sexes. The sex system, like the shoe system, is binary.

Why is this important?

As you’ve probably noticed, our society is struggling with questions relating to sex and gender these days. We’re rethinking boundaries that have long been set up with regard to sports, prisons, shelters, locker rooms, and so on, boundaries relying on the assumption that there are, in humans, two biological sexes. Some of those in favor of revising the boundaries question whether biological sex really is binary. In this essay, we’ve seen two reasons they give for their doubts.

To recap, some say “sex” is ambiguous, and refers variously to hormonal sex, or to genital sex, or to chromosomal sex, etc., and not one of these is binary. In reply, one should point out that these are markers of sex, and not themselves sex. In fact, each of these is defined in terms of the true, fundamental notion of sex.

And we’ve also seen that some say things like “sex is not a binary variable,” since there are really four things that can be going on in an organism when it comes to sex: male, female, both, or neither. In reply, one should point out that these are combinations of sex, but combinations of sex are not themselves sexes, just as combinations of shoes are not themselves shoes.

Neither of these arguments, then, gives us good reason to doubt that sex is, in fact, binary.

Organizations to Support

I’m informed by Dr. Emma Hilton that yeast can reproduce sexually, but via isogamy—gametes that are structurally similar. Yet not every gamete is compatible with every other gamete, and so there are a large number of “mating types.” Anisogamous species like ours, however, find themselves limited to two varieties of gamete, and two sexes.

Thank you for this. This is the clearest, most articulate expression I've seen yet of something that we all understand intuitively, but about which many of us find ourselves sputtering when confronted with obviously insane arguments to the contrary (e.g., "Oh, so when you say, 'females can have babies,' you must be saying barren and menopausal women aren't really women because they can't have babies!" and so on).

Love your papers! Keep up the good work!