Strong Boys and Flexible Girls

Over 60 years of research supports the biological basis for sex differences in physical fitness.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

James L. Nuzzo, PhD, is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer in the School of Medical and Health Sciences at Edith Cowan University. He is the author of over 70 peer-reviewed research articles in the field of exercise science. He writes regularly about exercise, men’s health, and academia at The Nuzzo Letter on Substack. He is also active on X @JamesLNuzzo.

PART 1

Getting a Grip on Childhood Sex Differences in Strength

“It is moreover impossible to prove that the differences in mean performances of men and women are the result of biology rather than education and training.” 1

“Feminists do not deny that bodily differences between women and men exist; rather, they claim that many, if not most, of the uses of these differences are ideological… Men have the advantage because all men’s bodies are stereotyped as bigger, stronger, and physically more capable than any woman’s body. Realistically, we know that a well-trained woman, a tall and muscular woman, a woman who has learned the arts of self-defense, a woman soldier, or a woman astronaut is a match for most men.” 2

The average adult man is physically stronger than the average adult woman, a difference that is both apparent to the naked eye and supported by extensive data. These sex differences in muscle strength correlate with differences in muscle mass. For example, in arm muscles, the average woman has 50 to 60 percent of the average man’s strength and muscle mass. In leg muscles, this figure is 60 to 70 percent.

But what about kids? Do sex differences in muscle strength exist among them? If so, at what age do they arise? Are these differences present at birth, or do they only appear after puberty? Could they be attributed to biology or socialization?

In 1985, Thomas and French conducted a seminal meta-analysis on childhood sex differences in physical fitness. They aggregated all available data on tests of fitness completed by boys and girls aged 5 to 17 across the United States.

One attribute they examined was grip strength. They discovered that post puberty, boys’ grip strength significantly exceeded that of girls. No surprise there. However, they also found that boys were stronger than girls even before puberty, albeit to a much lesser extent.

Thomas and French attributed adolescent sex difference in grip strength to biological changes that occur during puberty. However, they speculated that pre-pubertal sex differences in muscle strength were likely “mostly environmentally induced.” Consequently, they concluded that differences in muscle strength between boys and girls before puberty could “easily be eliminated if girls and boys were treated similarly.”

Thomas and French deserve credit for pioneering the use meta-analysis to quantify childhood sex differences in physical fitness. Nevertheless, their speculation that pre-pubertal girls are physically weaker than pre-pubertal boys due to social and environmental factors was questionable. Additionally, their analysis included grip strength data from only four studies, two of which were not even published in scientific journals. This limited data likely explains why they did not explore sex differences in kids younger than five years old.

Today, grip strength data in kids are plentiful, including in boys and girls under five years old. Despite this, contemporary researchers have neither attempted to update Thomas and French’s 40-year-old meta-analysis nor have they thoroughly addressed claims regarding the socialization of muscle strength before puberty.

Thus, I recently updated and expanded Thomas and French’s initial analysis, quantifying sex differences in grip strength from birth to age 16.

To indirectly explore the socialization hypothesis, I compared sex differences in grip strength across time and place. If socialization causes sex differences in muscle strength prior to puberty, then we might expect these differences to have narrowed over the past 60 years, given the increased opportunities for girls and women to participate in sports over that time. We might also expect sex differences in strength to differ between countries, reflecting differing customs and policies regarding physical activity for boys and girls.

I identified over 150 studies that contained grip strength data from more than 300,000 boys and girls who were tested in 46 countries. The studies were published between 1961 and 2023.

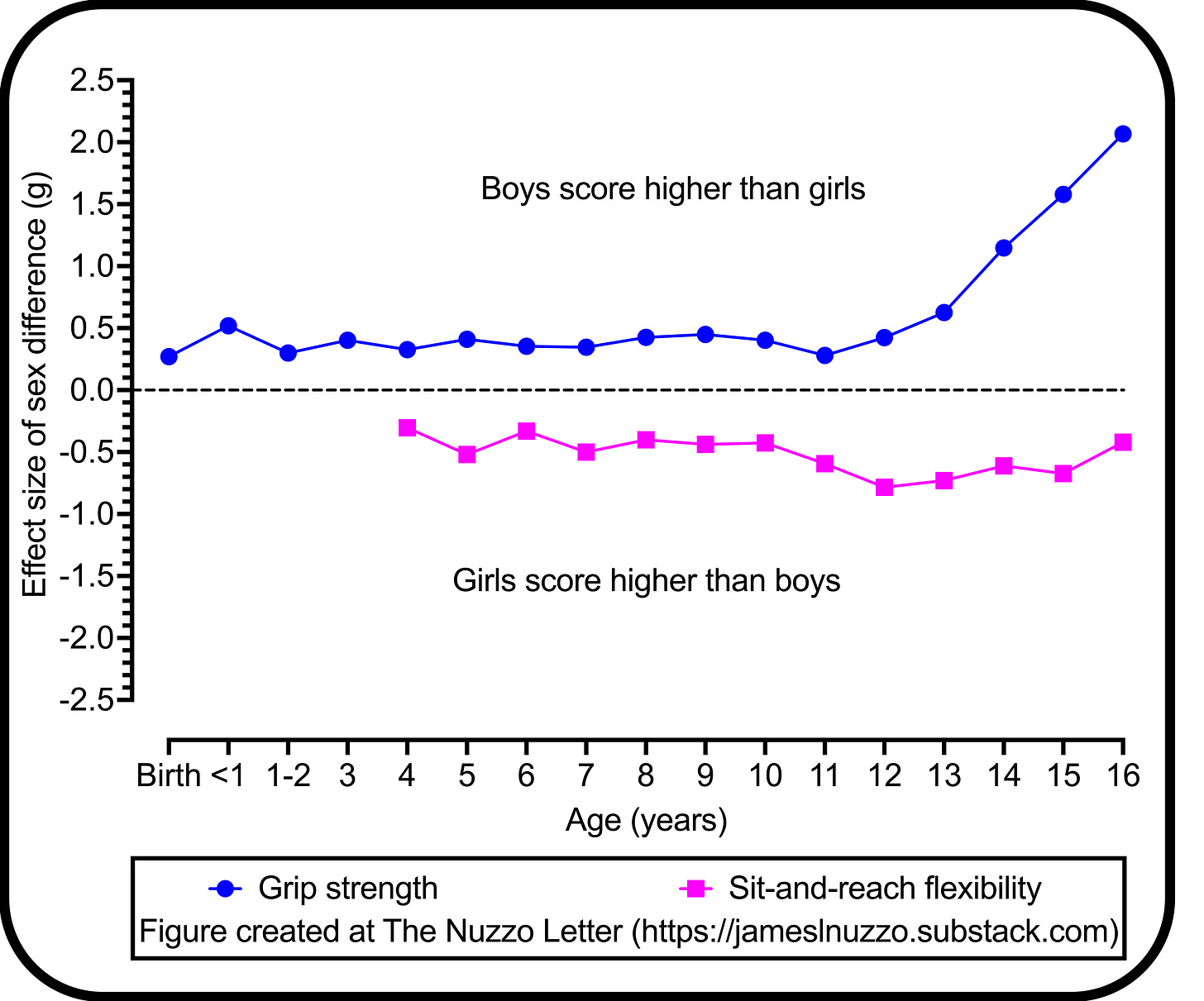

The graph below illustrates effect sizes of sex differences in grip strength at each year of development. A larger effect size indicates a greater sex difference. Effect sizes around 0.5 are typically considered moderate, with 0.8 considered large, and 1.5 or higher considered pretty damn substantial. For comparison, effect sizes for certain personality traits like agreeableness and neuroticism range from 0.30 to 0.50.

The graph shows that boys are consistently stronger than girls at all ages. From birth to age 10, the sex difference in grip strength is small to moderate, with girls having about 90 percent of boys’ strength. At age 11, this difference briefly narrows, likely because girls typically reach puberty before boys. However, by age 13, the sex difference begins to widen considerably, and by age 16, the difference is substantial, with the average girl possessing only 65 percent of the average boy’s grip strength. From other research, we know that the sex difference in grip strength continues to widen over the next few years, resulting in the average woman having 60 percent of the average man's grip strength by the time both sexes reach physical maturity.

Overall, the results confirm the initial observations by Thomas and French, but confidence in these results has substantially improved due to the much larger sample size examined (see the graph in the paper for the “tight” confidence intervals around the effect sizes).

However, results from the secondary analyses challenge the socialization theory put forward by Thomas and French. Across various countries, the sex difference in grip strength is broadly similar. For instance, among 5- to 10-year-olds, the effect size in China is 0.38, compared to 0.35 in the United States. Among 14- to 16-year-olds, the effect size in China is 1.61, while in the United States, it is 1.56.

Moreover, the size of the sex difference in grip strength has remained mostly stable since the 1960s. For 14-to 16-year-olds, the size of the sex difference has not changed over the past 60 years. Among 5- to 10-year-olds, there was no change between 1960 and 2010, but it narrowed slightly after 2010. I am unsure whether this slight narrowing among 5- to 10-year-olds is a real effect or merely a statistical fluke. Either way, the lack of a similar secular change among 14- to 16-year-olds suggests that once male puberty hits, the size of the sex difference prior to puberty becomes dwarfed.

So, what causes the sex difference in muscle strength in children and adolescents? For adolescents, the primary contributing factor is the 20- to 30-fold increase in testosterone that boys experience during puberty, which causes them to develop substantially more muscle mass than girls.

The cause of the sex difference in grip strength prior to puberty is less clear. Possible explanations include higher testosterone levels in boys than in girls in utero and during infancy, with higher levels during infancy correlating with greater growth velocity. Boys are taller and weigh more than girls until about age 11 (USA data), and both body height and body mass positively correlate with grip strength.

Childhood sex differences in body composition also likely play a role. Pre-pubertal boys have less fat mass, more fat-free mass, and lower body fat percentages than pre-pubertal girls. These sex differences in body composition become more pronounced during puberty, which is why the sex difference in muscle strength also amplifies at that time.

Finally, regarding the claim that sex differences in muscle strength arise from differences in treatment, education, and training, evidence suggests otherwise. Even when boys and girls at various pubertal stages are matched for the number of hours spent playing sports, boys still exhibit greater grip strength.

So much for socialization theory…

PART 2

Systemic but Muscle-Specific Sex Differences in Strength

Some critics might argue that focusing solely on grip strength biases the results in some way. This criticism is a bit of a reach, but it is true that the extent of sex differences in strength among adults varies depending on the muscle tested. Whether sex differences in strength in children are also muscle-specific or systematic is unclear. To address this question, I conducted a second, follow-up meta-analysis incorporating all available data on arm and leg strength in children and adolescents. The leg strength assessments included tests of the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves, while arm strength assessments excluded grip strength and focused on the biceps and triceps.

I identified over 30 studies that provided data from more than 15,000 boys and girls between the ages of 5 to 16.

The results show that, on average, boys are stronger than girls across all ages and the muscles tested. Similar to grip strength, the sex difference in arm and leg strength increases markedly during male puberty. However, the sex difference is more pronounced in arm than leg muscles. This is true at all stages of development. For instance, between the ages of 5 and 10 years, the average girl possesses 85 percent of the average boy’s arm strength, and 94 percent of his leg strength. Though puberty causes sex differences in both arm and leg strength to widen, the disproportionate male advantage in arm strength remains. Between 14 and 17 years of age, the average girl has only 65 percent of the average boy’s arm strength and 76 percent of the average boy’s leg strength. Thus, consistent with results in adults, men and women show more similarity in leg strength than in arm strength.

Overall, like the meta-analysis on grip strength, these results confirm that, on average, boys are stronger than girls at all stages of development. The results confirm that sex differences in muscle strength increase markedly with male puberty and are more pronounced in arm than leg muscles before, during, and after puberty. Childhood and adolescent sex differences in muscle strength are therefore systemic but muscle-specific.

PART 3

Hard To Stretch the Truth About Sex Differences in Flexibility

Findings from the first two meta-analyses indicate early sexual dimorphism in muscle strength, a fitness attribute boys might be expected to score higher on than girls based on known sex differences in adults. However, what happens with a fitness attribute where adult women consistently outperform adult men? To examine this, we have limited options, one of which is flexibility.

Flexibility refers to the intrinsic properties of body tissues that determine maximal range of motion of a joint without causing injury. Some researchers, myself included, view flexibility—particularly as measured by the sit-and-reach test—as an overrated fitness component. Nevertheless, flexibility remains a physical attribute that can shed light on the nature and development of sex differences.

Sex differences in flexibility of certain body joints are observable to the naked eye. Heaps of data illustrate that adult women tend to be more flexible than adult men, including higher rates of joint hypermobility in girls and women compared to boys and men. However, it remains unclear at what age these differences in flexibility appear and whether their magnitude changes throughout development.

To investigate this, I gathered as many studies as I could find that reported boys’ and girls’ sit-and-reach test results. Many readers may recall the sit-and-reach from physical education class, where one sits on the floor and stretches forward as far as possible toward, or beyond, one’s toes. This test primarily measures hamstring extensibility and, to a lesser extent, lower back extensibility.

The sit-and-reach is arguably the most frequently administered test of flexibility in human history. It was developed by Katharine Wells and Evelyn Dillon in 1952. In the decades since, millions of boys and girls worldwide have performed this test as part of school fitness batteries. Thus, the sit-and-reach offers a statistically robust way to study the sexual dimorphism of a fitness attribute throughout development.

I analyzed data from 95 studies that included sit-and-reach results from over 900,000 boys and girls aged 3 to 16 years. These studies were conducted in 38 countries and published between 1983 and 2023.

The findings indicate that girls consistently exhibit greater sit-and-reach flexibility than boys across all ages (see graph above). From ages 4 to 10, the sex difference in sit-and-reach flexibility is consistent and moderate in size. At age 11, the sex difference widens, presumably due to the onset of female puberty, and then the difference peaks at age 12.

However, unlike the sex difference in muscle strength, which continues to expand after puberty, the sex difference in sit-and-reach flexibility plateaus throughout much of puberty. It then begins to narrow, and by age 16, the difference is roughly the same size as it was before puberty. I also found that sex differences in sit-and-reach flexibility are similar between countries and have remained relatively stable since the 1980s.

Overall, results from this third meta-analysis confirm that sexual dimorphism in flexibility occurs early in development, is impacted by puberty, and is broadly consistent across time and place.

In children, the causes of the sex difference in sit-and-reach flexibility are not entirely clear. As far as social factors, girls participate more regularly than boys in flexibility-based activities such as yoga, gymnastics, and dance. Yet, sex differences in flexibility often appear before ages when rigorous exercise training is likely, and girls have greater flexibility than boys even when both participate in the same sports.

Biological factors likely explain sex differences in sit-and-reach ability among children and adolescents. Girls’ inherent biological propensity for flexibility likely contributes to their greater self-confidence in flexibility compared to other fitness attributes. This heightened self-confidence may, in turn, boost their interest and participation in activities that require flexibility.

In adults, men typically exhibit greater hamstrings muscle stiffness and a lower pain tolerance to hamstrings stretch. This increased stiffness is thought to be linked to men’s greater hamstrings muscle mass. Additionally, newborn girls have smaller spinal bones than newborn boys. This anatomical difference, which is believed to be an adaptation in females for supporting the fetal load in a bipedal posture, might contribute to increased spinal mobility among girls, thereby facilitating a greater reach in the sit-and-reach test.

GENERAL CONCLUSION

These three meta-analyses demonstrate that sex differences in muscle strength and sit-and-reach flexibility are evident throughout childhood and adolescence. For the first 10 years of life, these differences are small to moderate. Around the age of 11, girls narrow the sex difference in strength and widen the sex difference in flexibility, likely due to girls reaching puberty before boys. However, these shifts are short-lived. Once boys undergo puberty, they become significantly stronger than girls, and the sex difference in sit-and-reach flexibility returns to pre-pubertal levels. Moreover, these sex differences in muscle strength and flexibility are broadly similar across time and place. They have remained stable over recent decades and are roughly the same size in most countries.

At the beginning of this essay, I quoted multiple authors who, in one form or another, suggested that sex differences in physical fitness are primarily stem from sex differences in socialization. However, numerous lines of scientific research, including these three meta-analyses, indicate that human sex differences in physical fitness are largely biological in origin.

In my opinion, those who claim otherwise have a lot of explaining to do.

By the way—if you appreciate these research projects, you can still support them at the designated Go Fund Me page. Your support is greatly appreciated!

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoyed this article and know someone else you think would enjoy it, please consider gifting a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Of all the things I took out of this article, the one I appreciated the most, lol, is the admission that flexibility, particularly sit and reach, is overrated in fitness evaluation. I was always an athletic girl and then athletic women, playing soccer, volleyball, and jogging, cycling, and swimming in my spare time. And I was never that flexible, never able to touch my toes. Not until I took pilates (which I hated so we began weightlifting). And I was still one of the best players on the team!

I recall how as a girl even though I had endurance and could outlast all but one kid, the fastest sprinters were boys. And in tag, they always did the quick misdirections the best, so I could catch the girls and unathletic/ slower boys, but the most athletic boys were always out of my reach. Which is the point of sports - only the best compete.