The 2023 Dutch Debate Over Youth Transitions

Medical, legal, and cultural debate over the practice of youth gender transitions has come to the birthplace of the Dutch Protocol.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

This article was originally published on the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine’s website on November 19, 2023.

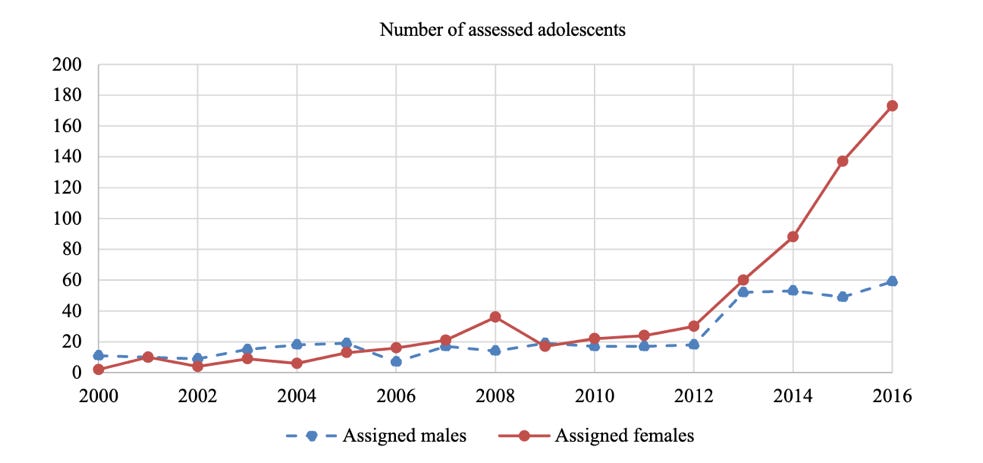

The Netherlands, like the rest of the Western world, has experienced an unprecedented increase in the number of youth seeking to undergo gender transition. Like the rest of the West, this sharp increase has been driven largely by adolescent females. Unlike the rest of the Western world, where this dramatic epidemiological shift has led to scientific debate about the practice of youth transition, the Netherlands practice has been insulated from scrutiny—until now.

However, three recent events in 2023—a medical publication in a prominent Dutch-language medical journal, a legal publication in the Dutch legal weekly journal, and a two-part documentary by BNNVARA, a liberal Dutch public broadcaster—suggest that the debate about the practice of gender transition of minors has finally reached the Netherlands. Below, we detail the key points raised in the debate, discuss the factors that contributed to the debate, and reflect on the significance of this debate in the Netherlands and its implications for the greater international reckoning about the practice of youth gender transition.

The Debate in the Netherlands: Key Takeaways

The highly medicalized approach for youth presenting with gender dysphoria has come under scrutiny in the Netherlands. The Netherlands is both the birthplace and the international center of expertise for the practice of youth gender transitions. As of 2023, there is growing Dutch debate in the medical, legal, and cultural contexts regarding the practice of youth gender transitions. The current practice of youth gender transitions in the Netherlands is guided by the 2018 Dutch Protocol.

The debate in the Netherlands is important for the rest of the Western world. The 2018 Dutch Protocol is based on the 2017 Endocrine Society and the 2012 WPATH "Standard of Care 7" guidelines. These same guidelines widely promulgated the practice of youth gender transitions in the rest of the Western world. Further, the Netherlands continues to shape the state of care for gender-dysphoric youth worldwide, as evidenced by the Dutch clinicians' active participation in WPATH "Standards of Care 8" published in 2022. As such, Dutch debates about "gender-affirming" treatments for youth have direct relevance to the practice of youth gender transitions in the rest of the West.

A growing number of Dutch and international experts are concerned that the potential adverse effects of puberty blockers — a treatment that is central to the Dutch Protocol — have not been adequately researched. There has been insufficient focus on adverse effects, particularly the effects of puberty blockers on brain development, cognition, and the possibility of a “lock-in” effect of what might otherwise be transient gender dysphoria. There is growing recognition that the impact of puberty blockers on the brain is largely unknown. Due to the sensitivity of the subject and the the possibility that findings may be negative, it appears uncertain that proper research into the effects of puberty blockers on the brain will be funded.

The Dutch critics have noted that the 2018 Dutch Protocol deviated from the original protocol in a number of important ways without providing any scientific justification for the changes. The 2018 Dutch Protocol did away with many of the eligibility restrictions in the original Dutch protocol. In the original version of the protocol, only adolescents with early-childhood onset of gender dysphoria were allowed to medically transition. However, the 2018 Dutch Protocol relaxed this and a number of other prior restrictions, while failing to provide an appropriate scientific justification for the changes. This is highly consequential, as the majority of youth transitioned under the 2018 Dutch Protocol today likely have post-pubertal emergence of gender dysphoria, and would not have qualified for gender transition based on the original criteria.

Several Dutch legal and ethics experts have opined that the current Dutch treatment guidelines are not “standard of care” in medical-legal context. To be considered standard of care, first and foremost guidelines should be evidence-based. In contrast, the 2017 Dutch Protocol was not based on a systematic review of evidence. There were other limitations, including a biased stakeholder team composition. The legal and ethics experts call for a proper guideline update, but note that ultimately, no medical guideline, no matter how well-written, may prove to be authoritative in this heavily ethically laden context. This is because the quesiton of whether gender transition is an appropriate societal response to a gender-incongruent child or adolescent (whose identity development is not yet complete) is largely an ethical, rather than medical, matter.

The Dutch critics of the current practice are calling for re-evaluation of the practice of youth gender transitions. A growing number of voices note that providing highly invasive medical and surgical interventions as the first and primary response to gender incongruence in youth ignores the findings of recent systematic reviews of evidence. These reviews have failed to find credible evidence of psychological benefits. Given the known harms (including, but not limited to, infertility and sterility), and the many more unknowns, the critics are questioning whether the Netherlands should consider aligning its policies and practices with Sweden, England, and Finland. This would entail reserving medical interventions to childhood-onset gender dysphoria and administering them in strictly research settings, while treating adolescent-onset gender dysphoria with psychological support.

Medical Debate

A recent publication in the Dutch Journal of Medicine questioned the validity of the “gender-affirmative” approach as primary treatment for gender dysphoric youth. The publication was a response to a clinical lesson written by a team of Dutch gender clinicians that was published in the same journal. The lesson described significantly increased volumes of gender dysphoric adolescents presenting for care in the Netherlands, and their many mental health comorbidities, including autism. The lesson referenced a “possible advantage” of puberty blockers, but acknowledged that the evidence is uncertain:

Various studies have shown that during puberty inhibition, there is a decrease in emotional problems, depression and suicidality, and an improvement in global functioning, although there are also studies in which no change was found. During medical treatment, guidance is provided by a psychologist; this may also have contributed to the reported positive effects.

Despite this careful language, all three cases of gender-dysphoric youth presented in the lesson started various forms of gender-affirming medical interventions. A young natal male with childhood-onset gender dysphoria was affirmed as a transgender female and prescribed puberty blockers. Two natal females with an ostensibly adolescent onset of gender dysphoria were affirmed as transgender males: one approved for menstruation suppression while awaiting a gender clinic consult, and the other approved to start testosterone.

The published lesson was preceded by the journal editorial which struck a substantially more cautious tone. The editorial highlighted the ethical concerns of providing treatments without knowing whether they help or harm in the long run and called for more extensive exploration of the etiology of a young person’s gender-related distress before initiating medical interventions. The journal’s Editor-in-Chief noted:

By treating without really knowing whether gender treatment will harm later, we have passed Hippocrates' "first, do not harm" point. The primacy now seems to lie with 'first, treat'. But harming and doing good are not separate. Nothing benefits that cannot harm, Ovid added to Hippocrates' words… This applies just as much to getting adhesions after successful abdominal surgery…as it does to possible long-term side effects of puberty blockers.

What is difficult for a good dialogue about this is that everything you say in the gender debate can be interpreted as an attack on supporters or opponents of early medical treatment. Shall we then replace 'first do no harm' and 'first treat' with 'first ask questions'? Primum rogare! From which maze is someone looking for an exit? What is he or she struggling with, in her or his environment?

The lesson also generated a critical peer-reviewed commentary along with a more detailed supplement. The authors of the commentary noted that the lesson suffered from five serious problems:

Problem 1: The lesson did not differentiate between childhood and adolescent-onset gender dysphoria. The original Dutch research only studied the childhood-onset presentation, and explicitly excluded youth with adolescent-onset gender dysphoria, which often occurs in the context of other mental health challenges. The authors of the commentary criticized the lesson for not discussing this point. In fact, all the patients presented proceeded with gender-affirmative interventions, regardless of the age of onset of gender dysphoria. Specifically, the autistic female teen with post-puberty onset of gender dysphoria was approved for testosterone—an indication that is not justified by the original studies that served as the basis for the Dutch protocol.

Problem 2: The unknown long-term regret rate for currently transitioning youth was not properly acknowledged. The lesson states that 98% of the adolescents prescribed cross-sex hormones, continue to use them “long-term.” This statement may lead one to believe that long-term regret rates (at least as evidenced by hormone discontinuation) are low. The authors of the critical commentary point out that the study cited as the source for the 98% continuation number cannot be used to assert low long-term regret. This is because the median follow up in the study was only 3.5 years for males and 2.3 years for females, and regret may take up to 10 years to emerge.

The authors note that the study's short-term follow-up indicates that a significant number of youth in the study presented to the gender clinic in the last several years. This group was found to be different from the earlier-presenting cases. The authors observe that it is “simply unknown what the regret percentage will be” in this novel group of patients.

Problem 3: The lesson failed to discuss the possibility that puberty blockers may impede, rather than facilitate, reflection. The clinical lesson presented puberty blockers as providing time for “further exploration.” The authors of the commentary argue that puberty blockers may also be setting a young person on a path for further medicalization. They note that only 1.4%-6.0% of Dutch youth stopped taking puberty blockers, with the rest – the overwhelming majority – proceeding to cross-sex hormones. While the Amsterdam UMC acknowledged that puberty blockers may not serve as a pause button but may instead serve to facilitate the continuation of the medical transitions as early as 1998, this possibility was not mentioned in the clinical lesson.

The concern that puberty blockers may have a lock-in effect, “trapping” a young person in the medical pathway was expressed in the Cass review in the UK. The mechanism for this effect is as yet unknown but may include halting psychosocial and sexual development. Of note, before puberty blockers became widely used, natural resolution of gender dysphoria sometime during puberty, and emergence of homosexual orientation in most affected youth were the most common outcomes.

Problem 4: The potentially negative effects of puberty blockers on brain development were not addressed. The clinical lesson acknowledged insufficient research into the effects of puberty blockers on the brain of gender-dysphoric youth but asserted that in contexts other than gender dysphoria, no adverse effects of puberty blockers on IQ have been observed. The critical commentary points out that this assertion is factually incorrect, as at least one study of youth treated for precocious puberty showed a significant IQ drop from 100 to 93 after just two years of puberty inhibition. Of note, the youth in the precocious puberty study were on average aged 9.6 (girls) - 11 (boys) when they started pubertal suppression—ages that are only somewhat younger or comparable to the current indication for pubertal suppression for gender dysphoria.

The commentary authors note that there are other concerning signals about cognitive effects in the literature. (A recently released Part II of the Dutch documentary, The Transgender Protocol, focuses on the unknown effects of puberty blockers on the brain.)

Problem 5: Reliance on outdated protocols. The clinical lesson referenced the Dutch care guidelines, “Somatic Transgender Care” (effectively, the 2018 Dutch Protocol) and “Psychological Transgender Care” (the psychological care guideline) as authoritative sources of information. The authors of the critical commentary note that these guidelines are now outdated. In addition, they are not based on a recent systematic review of the literature. The authors observe that recent NICE systematic reviews of evidence found the benefits of youth transition to be of very low certainty.

The commentary observes that the situation in the Netherlands is critical: there is an exponentially growing number of youth who want to undergo medical transition, the cause for this phenomenon remains unclear, and there is a lack of of credible evidence that youth gender transitions will improve quality of life in the long run.

The authors conclude with a call to restructure gender care for youth in the Netherlands similar to the actions taken by Sweden and Finland: providing extensive mental health support, while sharply restricting gender reassignment to a much narrower group and instituting it in only in research settings:

In our opinion, the Netherlands should therefore immediately radically reform gender care, following the example of Sweden and Finland. This would mean that hormones can only be prescribed as an ultimum remedium, in a strict research context and only to the original target group of the Dutch Protocol, namely: children with severe gender dysphoria from early childhood. For the large group of adolescents who first experience gender dysphoria at the beginning of puberty or even later, less invasive interventions, such as psychosocial support and treatment of additional psychological problems, should become the first-line intervention. After all, the starting point must be: primum non nocere.

Helpful Links

Clinical Lesson (Dutch)

Clinical Lesson (English-language abstract)

Editorial (Dutch)

Critical commentary (Dutch)

Critical commentary (English-language abstract)

“Somatic Transgender Care” (Dutch)

“Psychological Transgender Care” (Dutch)

Legal Debate

A recent paper published in the Dutch legal weekly journal, Nederlands Juristenblad (NJB), applied a judicial lens to the 2018 Dutch Protocol–the Netherlands’s current official guidance for treating gender-diverse youth–to assess whether the protocol would be considered a “standard of care” in civil litigation. For a clinician’s actions to be considered consistent with the “standard of care,” they must be judged to be in accordance with the insights of medical science and experience, and they must be the same actions that any reasonably competent clinicians of the same medical specialty would perform under comparable circumstances, using means that are in reasonable proportion to the specific purpose of the treatment.

The authors maintain that the relevant literature and case law indicate that courts should only accept a medical protocol as a starting point for the determination of a standard of care when the protocol is (i) evidence-based, (ii) has a limited ethical dimension, and (iii) has been arrived at in a properly designed process. They argue that when scrutinized by judges, the 2018 “Dutch Protocol” is unlikely to meet the threshold to be considered a standard of care because it falls short on these key dimensions.

The 2018 Dutch Protocol

The authors observe that the term “Dutch Protocol” has many meanings. It is used to describe the general approach, pioneered by the Dutch clinical team, to treating gender dysphoric youth using puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgery. It can also refer to specific recommendations, which have continued to evolve over time. The paper focuses on the most recent 2018 version of the Dutch Protocol, which effectively represents the Dutch national guidelines for medical treatments of gender-dysphoric youth.

Unlike prior versions of the protocol, which emphasized careful selection of subjects with childhood-onset gender dysphoria uncomplicated by mental illness, and enforced strict age requirements, the 2018 Dutch Protocol aligned with the Endocrine Society guidelines and WPATH Standards of Care 7 guidelines. The 2018 version of the Dutch protocol eliminated the key requirement of childhood-onset of gender dysphoria and introduced several other changes, such as lowering the age of eligibility for cross-sex hormones to 15, mastectomy to 16, allowing non-binary transitions, and adopting the ICD-11 diagnostic terminology, which no longer requires “distress.” SEGM briefly reviewed the 2018 Dutch Protocol in an earlier post, partially reproduced below.

The authors argue that the 2018 Dutch Protocol may not be deemed a standard of care because (1) it is based on an inadequate evidence base, (2) it inappropriately exerts medical authority in an area that is primarily a matter of ethics rather than medicine, and (3) a proper process was not followed to create it.

Inadequate evidence base

The authors note that the courts will only grant authority to a medical protocol if it is evidence-based. They observe the 2018 Dutch Protocol is not based on a scientific basis of systematic reviews of evidence. Further, they note that the UK NICE systematic reviews of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones found the certainty of benefits to be very low, using the international GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) standard, which is used for guideline development in the Netherlands as well. The authors also note that several other European countries that evaluated systematic reviews of evidence, subsequently concluded that the risks of gender-affirming interventions for youth likely outweigh benefits, and that the treatment should be considered experimental.

Further, the authors observe that the decision to drop the “childhood onset of gender dysphoria” eligibility requirement, present in the earlier versions of the protocol, was not supported by any published studies. This is highly relevant, as youth with adolescent-emergent transgender histories represent the most common presentation treated with the Dutch Protocol today. This challenge further compounds the pre-existing challenges in the seminal Dutch research, which came into sharp focus last year, raising the question of the benefits of gender transition even for classic, early-childhood onset of gender dysphoria cases.

Inappropriate medical authority exerted over a primarily societal ethics issue

Citing the Dutch Handbook on Health Law, the authors note that medical protocols have very little authority when considering ethically laden issues. The authors explain that when medical protocols address purely medical issues, they are considered to have significant authority because the protocol-writers possess specialty knowledge that others do not possess. In contrast, medical protocols that deal with largely ethical issues—such as elective abortion or euthanasia—have less authority because medical experts do not have an inherently superior knowledge of what is “ethical.” Medical interventions with significant ethical dimensions are decided through societal debate - not by medical experts.

The authors argue that the core of the Dutch Protocol is an ethical rather than a medical issue and as such, society rather than medical professionals should decide whether early intervention of gender transition is an appropriate societal response to a gender incongruent child. They discuss three issues central to childhood gender transition, which are strongly ethically charged. First, the scientific basis is weak, and it is unclear whether puberty blockers actually “lock in” the state of gender dysphoria that may have otherwise naturally resolved. Secondly, given the invasive nature of transgender treatments and their associated medical harms, it is unclear that early transition is preferable to giving children a chance to experience natural resolution of gender dysphoria at a later point. Thirdly, given the weight of the decision, it is highly uncertain whether children aged 9-14 can be regarded as competent to give consent, and how such consent interacts with the children’s right to an open future.

The authors note that unlike similarly ethically laden issues such as abortion and euthanasia, which were extensively debated in the Netherlands, the practice of adult gender transition was shielded from public debate—largely because it was such a rare occurrence in the past. However, the authors argue that now that the condition has become much more common, and the subjects include so many children and adoleslcents, such debates must play out in the public arena. Until then, the Dutch Protocol’s sanctioning of gender transition of gender incongruent minors carries little authority.

Inadequate process used to design the protocol

The authors explain that the 2018 Dutch Protocol committee did not follow the established process for developing a credible methodological guideline. A systematic review of evidence was not commissioned. Further, the team composition allowed for significant conflicts of interest, which unduly influenced decision making. The authors specifically focus on the influence of Transvisie, the Dutch patient advocacy group. The advocacy group took credit for several changes to the 2018 Dutch Protocol, such as lowering the age of mastectomy to 16 and limiting the role of psychological assessments.

The authors acknowledge the voices of transgender-identified stakeholders as important to the discussion. However, they point out the obvious omission of other important voices, such as those who may have struggled with gender issues but ultimately resolved them noninvasively, or those who felt they were harmed by transition, such as detransitioners. These critical omissions biased the development of the protocol.

Conclusions

The authors note that while gender transition may be associated with as yet unproven benefits, it carries undeniable risks:

The ability to have children naturally is affected in many cases. So-called fertility preservation by freezing eggs or sperm is a route with several possible complications and therefore has no guarantee of success; (b) sexual functioning, given the imperfections of the new sex organ, may be problematic; (c) because of the complexity of the techniques used, there is the possibility of serious medical complications and lifelong dependence on medical care; (d) the fact that people are recognizable as trans persons when engaging in physical intimacy can be perceived as problematic, not least in finding a partner.

When a child consents or assents to medical treatment with such significant risks and uncertainties, the authors aptly question: “What loyalty does the child feel toward his future self?”

The authors conclude by calling for the Dutch Healthcare Institute, which is ultimately responsible for approving guidelines, to take the lead in establishing a new clinical guideline. In the meantime, they suggest that the Netherlands consider making immediate changes consistent with those other European countries have made. Most importantly, they call for restricting eligibility for youth gender transition to early childhood-onset cases treated exclusively in clinical research settings. For adolescents with post-pubertal onset of gender dysphoria, the authors recommend that instead of gender transition, such youth should receive extensive psychological support and, in the case of co-occurring psychiatric conditions, appropriate mental health interventions.

Helpful Links

“Somatic Transgender Care” 2018 guideline

“Guideline for Guidelines” Dutch guidance for developing treatment guidelines

Cultural Debate

A progressive liberal Dutch public broadcaster, Zembla, released a 2-part Dutch-language documentary “The Transgender Protocol.” Part I of the documentary investigates the scientific foundation that formed the basis for the Dutch protocol. Part II examines the effects of puberty blockers on a child’s brain. The documentary strikes a distinctly concerned tone. The documentary generated debate with Dutch transgender advocacy groups, to which the public broadcaster later responded by re-asserting its concerns and the decision to run the documentary.

Zembla Documentary

Part I of the Zembla documentary challenges the assertions that the Dutch Protocol is safe and effective. The documentary covers several important points, including the:

Highly invasive nature of the interventions: The treatments used in transgender medicine are recognized as highly invasive, with irreversible lifelong consequences.

Detransitioner stories: The documentary profiles young patients treated according to the Dutch Protocol who no longer identify as transgender and are now left with irreversible changes to their bodies.

International criticism: The investigative reporters interview three international experts (Sweden, Finland) who state that the evidence is insufficient. The experts note that in other areas of medicine, such low-quality evidence would not be permitted to serve as the basis for such highly invasive medical and surgical interventions for youth.

Dutch criticism: Five Dutch experts (four methodologists and one professor of child psychology) explicitly declare that the evidence is insufficient.

Insufficient debate: Of the five researchers interviewed, only one felt he could be on camera discussing his concerns, and at least one researcher was directly discouraged from criticizing the protocol by his academic employer due to the fear that the topic is too “sensitive.”

The much shorter Part II of the documentary recaps the key issues from Part I and homes in on the question of the effects of puberty blockers on a child’s brain. The documentary concludes that there is an alarming lack of research into potential adverse effects:

Potential adverse effects of puberty blockers on the brain were hypothesized from the start, with plans to thoroughly research their effects. The documentary replays a radio clip from 2006 in which the Dutch gender clinic researchers discuss a plan to conduct thorough research: “A lot of development takes place in the brain during puberty, also under the influence of sex hormones, but no one knows exactly. We plan to investigate the effect of delaying puberty on brain development.”

However, the research that took place was woefully inadequate. The documentary features the single 2015 Dutch study that concluded that puberty blockers had no effects on the brain. The journalists interview a neuroscientist who co-authored the study. The neuroscientist observes that the study’s very small sample size and limited outcomes do not allow for the conclusion that puberty blockers have no effect on the brain. The neuroscientist notes that “recent animal studies have shown that puberty blockers can indeed have an effect on the development and functioning of the brain.”

The Amsterdam UMC acknowledges research limitations but argues that the alarm is not justified. The Amsterdam UMC clinic researchers are not as concerned about the lack of research of puberty blockers on the adolescent brain, arguing that educational attainment appeared unaffected relative to children’s baseline IQ scores. (Of course, IQ is but one measure of brain functioning, and educational attainment is, at best, an indirect measure of IQ.)

Lack of research funding and “zeitgeist” prevent additional research about the effects of puberty blockers on the brain. The neuroscientist interviewed in the documentary explains the sensitivity of studying the impact of puberty blockers on brain development and adolescent cognitive functioning: if it turns out that the effects are negative, this treatment pathway may no longer be considered as justified.

Criticism from Dutch transgender advocacy groups and the broadcaster’s response

In anticipation of the documentary, Dutch transgender advocacy groups expressed extreme discontent. They issued a 10-point statement, in which they asserted that because transgender is an internal state, only children themselves can determine whether they are transgender. They further opined that the indication for treatment is not the diagnosis, but a child’s wish for such treatments, provided that the child and/or their guardians are fully informed about the risks and benefits. The group insisted that the existing evidence is already sufficient to conclude benefits and asserted that requiring higher-quality evidence for this area of medicine is both a double-standard and not feasible, because such research would invariably be unethical.

The advocacy groups dismissed the significance of the international changes. They noted that Sweden’s, Finland’s, and England’s recent “reticence” to gender-transition youth and their “apparent deviation from the Dutch Protocol,” should not be considered a “normative view.” They noted that Sweden and Finland were laggards in transgender care for youth, having started the care 20 years after the Netherlands. The groups were particularly dismissive of England’s “curtailing of transgender care for adolescents”:

The Cass Report from England leans on the NICE review for assessment of the evidence for use of puberty inhibitors. The conclusion that no policy recommendation can be made on the basis of that evidence does not correspond with the assessment of the WPATH (World Professional Association of Transgender Health). Moreover, it is not known which “experts” conducted the review and therefore it cannot be ruled out that political or ideological considerations played a role in the design and analysis of the review.

The advocacy groups briefly addressed the sharp increases in the numbers of youth presenting for care, asserting that “the increase in youth demand for care is most likely to be explained by the removal of barriers due to decreased stigma and better access to care.” As for the switched sex ratio, strongly favoring adolescent girls, the groups asserted that when averaged across all age groups, the sex ratio is balanced. Further, in contradiction to the sharp increases in the numbers of gender dysphoric adolescent females documented by all reporting gender clinics in the West, including the Dutch gender clinic, the transgender advocacy groups asserted that “there is no so-called explosion of trans boys according to the WPATH in its new Standards of Care.”

The Dutch public broadcaster which produced the documentary, provided this response:

It is very important that people who rely on gender care receive the right information and are helped properly and carefully. Every person has the right to that. The Dutch protocol has been tested on a specific patient population. The current patient group differs in crucial ways from the group on which the protocol was tested. Finnish and Swedish psychiatrists who have extensive experience with gender care express sharp criticism of the way the Dutch protocol has been applied in recent years.

According to these doctors and the health authorities in their countries, there is insufficient evidence on which to base partially irreversible treatments. Especially because it concerns minor and vulnerable patients. Authorities in countries such as the United Kingdom and Denmark have also changed healthcare for this reason. And in other countries, such as France, doctors and governments have expressed concern. Investigative journalism such as Zembla aims to uncover facts and can actually lead to better care and a better position for vulnerable groups.

Helpful Links:

The Transgender Protocol Documentary

The Transgender Protocol, Part I

Part I, unofficial, English subtitles (SEGM has not verified accuracy of the translation)

The Transgender Protocol, Part II

Part II, unofficial, English subtitles (SEGM has not verified accuracy of the translation)

Factors Contributing to the Dutch Debate

The practice of youth gender transition in the Netherlands has avoided scrutiny largely because of the belief that unlike other Western countries, which saw an explosive growth in the numbers of adolescent-onset gender dysphoria complicated by mental health comorbidities in recent years, the Netherlands has been immune from this trend. Another likely reason for the lack of debate was that the care was centralized in a single centre that pioneered the practice, the Amsterdam UMC, instilling confidence that a group of preeminent gender clinicians could scale the practice safely.

Both of these assumptions were significantly challenged in the past year.

The marked change in gender dysphoria presentation in the Netherlands has finally been acknowledged. As of 2012, there were about 50 Dutch youths seeking gender reassignment per year. This number began to increase sharply around 2013, with a continued upward trend. A report commissioned by the Dutch government, which analyzed waitlist data, estimated that there were 900 new annual requests for puberty blockers alone—separate and distinct from the young people treated with cross-sex hormones only. Although the precise numbers of youth referrals are not available, it is clear that the Netherlands is subject to a similar epidemiological trend observed in the balance of the Western world: namely, skyrocketing numbers of adolescents presenting with a wish for gender transition, the preponderance of whom are natal females.

Despite the sharp rise in the number of cases and the change in sex ratios strongly favoring females which began around 2015, as recently as 2020 the Dutch researchers continued to believe that the newly-presenting cases were essentially identical to the earlier-presenting cases for whom the Dutch protocol was originally designed. This suggested no urgent need to re-evaluate the practice of youth gender transitions outlined in the Dutch protocol:

The described findings have clinical implications for providing early medical interventions. Since the assessed adolescents are so similar on most relevant characteristics over the years, this provides confidence that early medical treatment may also be helpful for recent referrals. It is likely that previously found results regarding the effectiveness of the Dutch protocol that includes puberty suppression as part of a multidisciplinary approach [13, 14], can be generalized to the transgender adolescents who currently apply.”(Arnoldussen et al., 2020, p. 7)

However, a 2022 re-analysis of the population of Dutch youth presenting for care by the same authors resulted in markedly different conclusions. The newly presenting youth were older, had significantly less gender incongruence in childhood, were “more dissatisfied with various aspects of their bodies”, and had more psychological problems. The researchers recognized that the presentation of youth gender dysphoria had changed in a significant way and acknowledged the need for “more tailored care.” Although not yet a call for a fundamentally new approach, this was an acknowledgement of the inaccuracy of the prior assumption that currently presenting youths can be confidently treated with the protocol designed for markedly different earlier cases:

This study has several clinical implications. The differences in demographic, diagnostic, and treatment characteristics, childhood gender nonconformity, and body image among adolescents from the older and younger presenting group argues for more tailored care. To ensure that each adolescent receives the treatment that best suits them, it is important to thoroughly explore all aspects of gender and general functioning with all adolescents before making decisions about further treatment [40]. The conclusion of a previous study that gender-affirming treatment earlier in life may have benefits is not necessarily founded for everyone [20].”(Arnoldussen et al., 2022, p. 8, emphasis added)

The volumes increased beyond the capacity that the original Amsterdam UMC clinic could effectively manage. Until 2018, the Amsterdam UMC clinic was effectively the only center providing transition services to youth. However, the clinic’s capacity was pressured as the numbers of youth presenting for care began to explode and the waitlist grew to 2 years or longer. As a result, more clinics began to provide care for transgender-identified youth. In addition to adding a second UMC clinic, Radboudumc UMC became a site for transgender care for youth. Further, a number of mental health providers outside the UMC system began to provide diagnostic assessments.

The following additional factors likely contributed to the debate in the Netherlands:

Detransitioners emerged. There is growing awareness of detransitioners internationally and in the Netherlands. A young man named “Maarten,” who transitioned at 16 to live as a woman, claims that transition “destroyed his life,” and has engaged a lawyer to explore possibilities for compensation. A small number of Dutch detransitioners have also spoken on social media.

The foundational research came under scrutiny internationally. The studies that underpin the practice youth gender transitions have come into sharp focus recently. The studies highlighted the fact that the Dutch protocol was never designed for or tested as treatment for adolescent-onset gender dysphoria. Further, a close examination of the original Dutch studies suggested that there is no credible evidence that even the youth with childhood-onset gender dysphoria benefit from transition. This finding was concurred with the NICE systematic review of evidence, which found the seminal Dutch puberty blocker study yielded only very low certainty of benefits, due to the critical risk of bias in the study design.

More diversity in clinical opinions within the Netherlands has emerged. As more providers become involved beyond the original Amsterdam’s UMC team that pioneered the treatment and to date has led the Dutch research, the views of the Dutch medical community are becoming more diverse. One of Radboudmumc UMC’s leading clinicians recently expressed caution: "It is wonderful that the transgender [treatment] trajectory exists, but you must use everything that is available to prevent medical intervention…These puberty hormones normally initiate psychosexual development. If you inhibit them, the children hardly have that development. I think that is a great concern.”

European changes can no longer be ignored. Several European countries, including Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark, and UK have either sharply curtailed the practice of youth transitions, or have raised serious concerns about the practice, following systematic reviews of evidence. These changes did not go unnoticed in the Netherlands.

SEGM Take-Away

The importance of the debates about the practice of youth transitions in the Netherlands cannot be overstated. The Netherlands is the birthplace of the Dutch Protocol—the practice of medically transitioning minors. The clinic which pioneered the treatment, the Amsterdam University Medical Center/UMC (formerly VUmc), has become an international center of expertise for youth gender transition. The 2018 Dutch Protocol is based on WPATH SOC7 and 2017 Endocrine Society guidelines, which are the same guidelines that widely promulgated the practice of youth gender transition in the rest of the Western world. Importantly, the Amsterdam UMC is also actively shaping the approach toward care for gender dysphoric youth worldwide: the Dutch clinicians contributed to “virtually every chapter of the most recent (eighth) edition of the WPATH Standards of Care for transgender care.”

This is not the first debate about the practice of youth transition in the Netherlands. In late 1990s, the practice of youth gender transition was hotly debated in the media, albeit for a brief period. The Dutch Ministry of Health put an end to the debate in just a few weeks (as documented in a recently-published book on the history of the Dutch protocol), issuing the decision that the practice was ethically acceptable because it was “meticulously crafted,” “fixed,” and because “treatment… efficacy is not questioned in the current state of science.”

It could be argued that the 2023 state of science has cast doubt on the treatment efficacy, while the argument that the protocol is “fixed” is no longer accurate. The criteria have continued to evolve, often without a well-documented scientific justification or proof of safety and efficacy. Further, the 2018 Dutch Protocol which is recognized by the Amsterdam UMC as the Dutch national treatment guideline, acknowledges that it deviated from the original premise, and instead “align[ed] with international guidelines such as Standards of Care released by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) (Coleman, 2012) and the Endocrine Society's Guidelines (Hembree, 2017)… .” This indicates that the 2018 Dutch Protocol not only suffers from its own unique problems discussed above, but likely inherited the well-documented severe methodological problems of the WPATH SOC7 and the problematic 2017 Endocrine Society’s guidelines. Importantly, the updated 2022 WPATH SOC 8 guideline has also recently come under sharp criticism from evidence-based medicine experts due to its many methodological failures, including the failure to base the recommendations for treating adolescents on any systematic reviews of evidence.

The Dutch debate has just begun. To date, acknowledgment of the weak evidence base and the changing population base has not resulted in an official change in treatment approaches. Whether the Dutch Ministry of Health will heed the suggestions of recent critical publications in the Dutch professional and popular press remains to be seen. However, the fact that the 2018 Dutch Protocol, which was slated for updating in the summer of 2023, has not yet been updated, may signal recognition that the changes required to bring the protocol in line with the principles of evidence-based medicine may be more substantial than originally anticipated.

Reality’s Last Stand is 100% reader-supported. If you enjoyed this article, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below. Your support is greatly appreciated.

The debate should never have gotten passed the use of the word "transitioned". It is impossible to transition from one sex (or gender) to the other. This is a scientific fact. What we can and should focus on is the mental anguish and confusion so many people are experiencing. This is a psychological and sociological problem, i.e., not biological. Moreover, it is one thing to facilitate an adult in surgically and chemically altering his/her body, but a morally reprehensive position to advocate and facilitate in any way doing this to a child. There is no debate.

Mass child sterilization and genital mutilation is probably a bad idea..... who would have thought? Oh, wait, every sane human for all of time. The insane ones pushing child genital mutilation and sterilization are never the good guys, and it’s not different this time.