Why Recreational Fitness Data on Trans Athletes Can’t Set Elite Sports Policy

What a widely cited BJSM paper actually shows—and why it doesn’t answer questions about elite competition.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

James Smoliga, D.V.M., Ph.D., is a professor at Tufts University School of Medicine who studies translational science, sports medicine, and how scientific evidence is applied in clinical practice and public health policy. He writes the Substack newsletters “Beyond the Abstract,” about the intersection of research, academia, and society, and “Human Limits,” focused on sports science.

A new paper in the British Journal of Sports Medicine has been making the rounds this week, promoted as evidence that sex differences in athletic performance largely disappear once testosterone is suppressed.

The headline version goes something like this: After hormone therapy, performance differences shrink. Therefore, biological differences must not matter very much.

On first read, that sounds plausible. Reasonable, even.

And to be fair, the study isn’t junk science. It has real strengths: a large pooled analysis, longitudinal hormone measurements, objective fitness testing, and—in some of the included studies—repeated assessments over time. On the surface, this is careful, methodical work.

But the paper quietly answers a very different question than the one people are using it to settle.

This is not a study about athletics or competitive sports performance. It’s a study about general physical fitness.

And that mismatch—more than anything about hormones or politics—is where the problem begins. The authors conclude that there is no evidence of “inherent athletic advantages for transgender women over cisgender,” a claim that goes well beyond what their data can actually support. That’s because the study is looking at recreational fitness, while elite sport lives in an entirely different physiological universe.

What the Study Actually Measures

Start with who’s being tested, and how.

These are not elite athletes. They’re not NCAA runners. They’re not national-level competitors. The participants are mostly:

military personnel

recreationally active adults and “amateur” athletes

In other words, people with mild to moderate training loads, often performing general fitness tests. Think push-ups, grip strength, VO₂ max, and 1.5-mile runs. For military recruits, these tests exist to ensure basic physical readiness for job-related tasks—not to measure athletic performance in a competitive sense.

To keep things concrete, consider the studies using the 1.5-mile run.

In Chiccarelli et al (2023), the average 1.5-mile time for women was 14:36. Transgender women (males who identify as women), by contrast, had a baseline time of 12:00. That’s almost identical to the men’s average in the study (11:59).

After up to four years of hormone therapy, transgender women’s 1.5 mile run times slowed to about 14:34, nearly matching the women’s average. In other words, after several years of cross-sex hormones, performance converged.

Roberts et al report a similar pattern. Transgender women ran 1.5 miles in 11:48 before treatment and about 12:45 after two to two-and-a-half years of cross-sex hormones—still faster than the female group in that study.

So yes, transitioning from male to female is associated with slower 1.5-mile run times. And this point is important: suppressing testosterone clearly reduces performance. If you take an elite male athlete and remove testosterone, performance will almost certainly decline. No serious person disputes that.

But neither study followed the female participants over time as matched longitudinal controls. Instead, the comparisons were largely made against population averages or separate groups.

That may sound like a technical quibble, but over two to four years, a lot can change. Training habits shift. Body composition changes. General fitness levels rise or fall. Any of that can affect performance. Still, this is a relatively minor concern compared to the larger problem.

And here’s the larger problem: this is fitness, not sport.

Yes, the participants engage in physical training. But these studies are not looking at athletes deliberately training at high intensity to optimize competitive performance in sports.

To see why this matters, consider Beatrice Chebet, the women’s world-record holder in the 5,000 meters. Her time is 13:56. That’s more than double the distance—about 3.1 miles—covered in roughly the same time it takes participants in these studies to run 1.5 miles.

In other words, she isn’t just a little faster. She’s operating on a completely different physiological plane than the “fit” people in these studies.

The women in these studies are not out of shape, but they aren’t athletes either. And that distinction isn’t merely semantic. Once you move from general fitness to elite competition, the factors that dominate performance change dramatically. (For context, the men’s 5,000-meter world record is 12:35).

What all of this means is that the BJSM paper is effectively examining general physical readiness in mildly trained adults under hormone manipulation. That’s a perfectly legitimate scientific question, but it is not the same as asking how much athletic performance changes when hormone therapy is applied to highly trained athletes competing at the limits of human performance.

We wouldn’t study the driving habits of daily commuters and then use those findings to set safety policy for Formula One drivers. Yet that is, in essence, what’s happening here.

A 14-minute 1.5-mile run isn’t an elite performance test. It’s a general fitness test. At that pace, a wide range of reasonably healthy adults overlap (more on that in the next section). Hormone-mediated biological limitations haven’t begun to show up yet.

Elite sport is different. It pushes athletes to their physiological ceiling—maximal oxygen delivery, maximal muscle power, minimal margins. Near those limits, small biological differences stop being small. They decide podium placement.

And those differences—observable only in elite populations performing at the edge of human capability—are what should drive policies aimed at preserving competitive fairness.

So even if hormone therapy may equalize recreational fitness metrics, it does not demonstrate biological equivalence at the ceiling. And that ceiling is where elite sport is actually decided.

The Mistake Most Interpretations Make

Most debates about performance assume differences behave like a single number.

They don’t.

Athletic performance is a distribution, and where you sample that distribution changes everything.

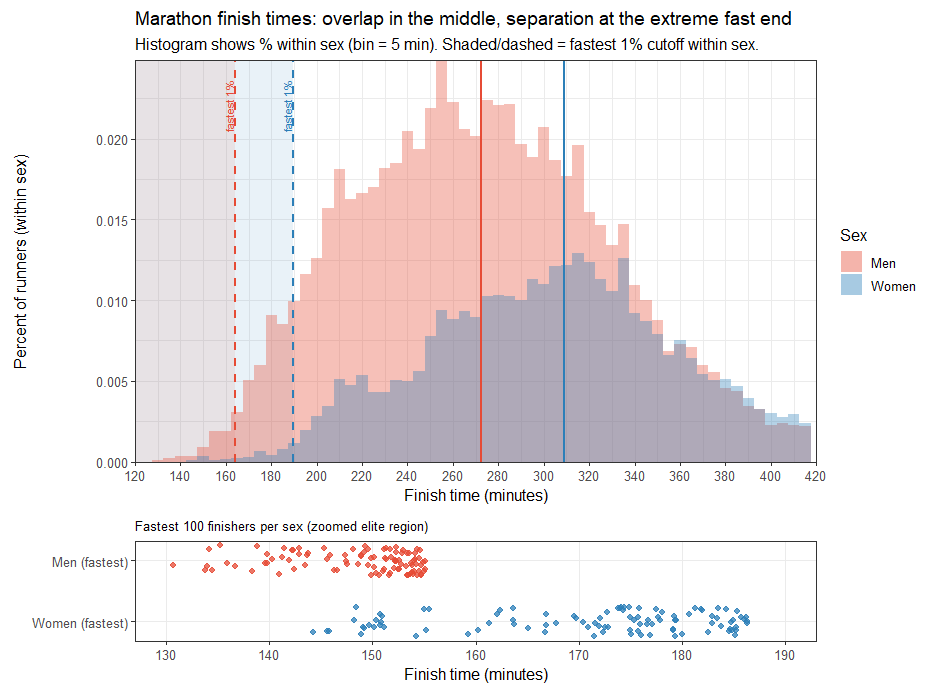

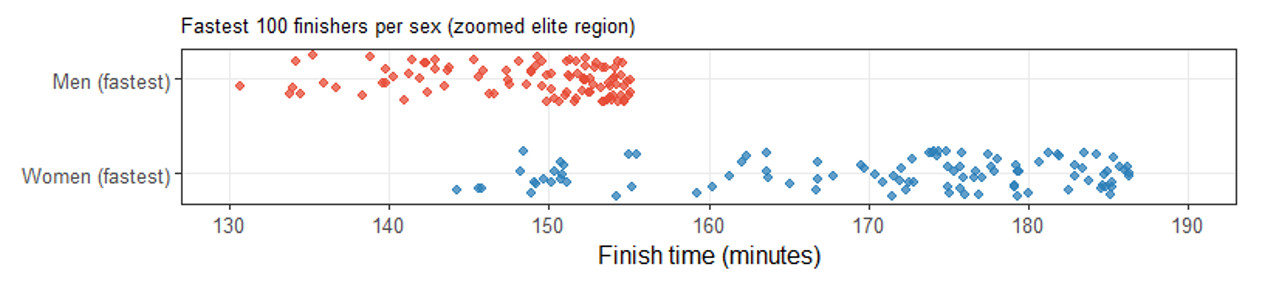

To illustrate this, I pulled a large public marathon dataset and plotted men’s and women’s finishing times.

Here’s what the distribution actually looks like:

The top panel shows the full population. Each bar represents the percentage of runners within each sex who finished in a given time range. The solid lines mark the median—the “typical” runner.

And right away, something important jumps out.

Men and women overlap—a lot. The curves largely sit on top of each other. The medians aren’t wildly different. The median male finished (red line) in about 275 minutes—roughly four and a half hours. Plenty of women ran faster than that. Likewise, many men finished slower than the median female runner, who clocked in around 310 minutes, just over five hours.

If you stopped here, you might reasonably conclude: Men and women aren’t that different.

For recreational runners, that’s largely true. On average, men finish about 30 minutes faster, but there is substantial overlap, and many women beat many men.

The mistake comes from assuming that what’s true in the middle of the distribution remains true everywhere else.

Now look at the dashed lines, which mark the top 1 percent of male and female finishers. On the surface, the separation looks similar to what we saw at the median. But to understand why it matters, you have to zoom in on the bottom panel.

Those dots represent the fastest 100 finishers—the extreme tail of the distribution. Only a small fraction of them ever contend for podiums, records, or prize money. Those are the athletes competition policy actually affects.

And here, the overlap nearly disappears.

The fastest men cluster far to the left. The fastest women cluster clearly to the right. No statistics are required. You can just see it.

That contrast is the entire point. Elite sport does not sample the middle of the bell curve. It samples the extreme tail—where small physiological differences suddenly matter a lot.

Studying the middle (as the BJSM article focuses on) and making claims about the edge is is not how competitive policy should be built.

The Recipe for Sports Performance

This isn’t mysterious. It’s just physiology.

Athletic performance isn’t the result of one ingredient. It’s the product of a layered “recipe” of physiological traits working together.

Genetics and early development establish the basic hardware. Puberty then permanently sculpts that hardware—heart size, lung capacity, skeletal structure, limb length, lever arms—in ways that are at least partly irreversible. Those developmental changes largely determine an athlete’s physiological ceiling: the maximum performance they can ever reach.

And that ceiling is what competitive sport actually tests. Not average fitness. Not casual training responses. The limits.

Adult hormone levels, by contrast, are more modulatory. They affect recovery, muscle and connective tissue maintenance, and—crucially—how efficiently the body adapts to training. But intense, sustained training is the mechanism that reveals where the biological ceiling actually lies.

This distinction matters because recreational fitness studies—the bulk of those included in the BJSM analysis—and elite sport operate in entirely different biological worlds.

In recreational populations, training varies widely and most people are nowhere near their physiological ceiling. Lifestyle noise and modifiable factors dominate. Many marathoners who finished in around 275 minutes could run 10, 20, or even more percent faster if they devoted their lives to training the way elite athletes do.

That isn’t an insult or calling them lazy. It’s just reality. Elite marathoners routinely run 90 or more miles per week for many years, layering in mentally and physically punishing interval sessions and threshold workouts. Most recreational runners aren’t training at that volume or intensity, nor should they feel any obligation to.

At the elite level, everyone is already training at or near their maximum. Training variability shrinks, and what remains are the hard limits set by biology and development. At that point, training no longer masks biological differences—it exposes them.

The best men run faster than the best women. Even “pretty good” males (i.e.,top American high school boys) often run faster than the best women. That’s just biology.

This is why the middle of the bell curve and the extreme tail aren’t just slower and faster versions of the same thing. They are, functionally, different physiological worlds.

I’ve focused here on running, but the same logic applies to other traits examined in these studies. Removing testosterone and adding estrogen may reduce grip strength in transgender women, bringing average values closer to those of biological females. But if both groups were subjected to serious, competition-focused training, individuals who went through male puberty would likely retain at least some performance advantage.

We can’t prove that from the available data—and that’s precisely the point. We also cannot assume the advantage disappears. The existing studies simply never test elite athletes operating near their physiological limits. They test people far below them.

The bigger point is that training has an enormous effect on maximal performance, and the BJSM study isn’t measuring that. It’s measuring how hormone manipulation affects basic fitness, often alongside modest training.

If the goal is to inform policy for elite sport, the relevant question isn’t how hormones affect recreational fitness. It’s how hormones interact with years of high-level training at the edge of human performance.

Adult Hormone Levels Are Permissive, Not Determinative

This is where many discussions go off the rails.

People implicitly think the relationship is simple:

hormones → performance

But that’s not how sport works.

The real chain looks more like this:

hormones → capacity to adapt → training response → performance

Hormones mostly act upstream. They shape how much muscle someone can build, how quickly they recover between hard sessions, and how much training stress they can absorb over time. Faster recovery means more high-intensity workouts. More high-intensity workouts mean greater cumulative adaptation.

This is also why performance-enhancing drugs work the way they do. They don’t magically turn someone into an elite athlete. They improve recovery and adaptation, allowing athletes to train harder, more often, and for longer—and to reap the benefits of that training.

No one believes you can take testosterone and instantly become elite. You still have to train brutally hard for years. Drugs amplify adaptation; they don’t replace it.

Which is why all of the following can be true at the same time:

a well-trained woman can beat an untrained man

a well-trained woman can beat an untrained man even if he’s using PEDs

a highly trained woman can beat a moderately trained man, even if he’s using PEDs

Halfway-decent female college distance runners (i.e., 17:45 5K) can beat most male entrants at any given local road race, even those who regularly train

But a highly trained woman will still not match a highly trained man, because of differences in the biological ceiling. That is why world records differ between men and women in virtually every sport.

Training differences dominate until biological ceilings come into play. Then biology decides.

Among recreational runners, the gap between someone finishing a marathon in 3.5 hours versus 4.5 hours is mostly about training. A woman running 60 structured miles per week can easily beat a man running 20, despite his biological advantage. Likewise, a man running 60 miles per week will almost certainly beat a man running 20. At this level, training volume and quality overwhelm biology.

But change the conditions, and the outcome changes.

Take a world-class male and a world-class female. Give them the same coach, the same training program, the same resources, and the same commitment. The male will win—by a lot. That isn’t because elite athletes train differently in some fundamental way. At that level, training volume and intensity distributions are already broadly similar. What separates outcomes are biological differences set by development.

Suppressing testosterone in adulthood can absolutely shift general fitness and recreational performance. That is exactly what the BJSM study demonstrates.

Take a biological male from the middle of the marathon distribution, suppress testosterone, and performance moves closer to that of a woman from the same middle of the distribution.

But elite sport isn’t decided in the middle. It’s decided at the biological ceiling, which is mostly shaped by genetics and development (i.e., puberty) not by day-to-day adult hormone levels. Altering hormones in adulthood, even for years, is very unlikely to fully remodel structures set during development.

That means equivalence between “transgender women” and biological women cannot simply be assumed. At best, the size of any remaining advantage is uncertain—and small residual differences are precisely what decide elite outcomes.

We would expect suppressing testosterone in an elite male athlete to reduce performance. The question is: by how much? We don’t know. The BJSM study doesn’t answer that question, because it never tests elite athletes near their limits.

It is likely that some athletic advantage persist even years after testosterone suppression—especially once serious, high-volume training is layered onto that physiology.

Studies limited to mildly trained populations are therefore asking the wrong question if the goal is to inform competitive sport. They tell us how hormone therapy affects everyday fitness, not how performance ceilings change under elite training conditions.

The Other Problem Sports Science Rarely Admits

There’s one more wrinkle that almost no one outside elite sport fully appreciates.

At the highest level, tiny differences decide everything.

A one-percent performance change sounds trivial in everyday life.

In sprinting or distance running, it’s the difference between winning and not even making the podium.

Ten seconds versus 9.85 in the 100 meters is the difference between gold and watching from the stands.

Consider the photo finish at the 2025 World Athletics Championship marathon (unable to show image due to copyright). After 26.2 miles, the top two runners crossed the line separated by just 0.03 seconds.

Now imagine that one of them had a 0.5 percent advantage. Over a marathon, that translates to roughly 40 seconds.

That’s the reality of elite sport. Small advantages don’t stay small. They turn into medals, records, and margins of victory.

But here’s the paradox: effects that matter enormously in elite sport are often scientifically hard to prove.

Elite samples are tiny. Day-to-day performance can vary by one or two percent. And the advantages that decide outcomes are often fractions of a percent.

So when a study reports “no statistically significant difference,” what that often means is “we didn’t have enough power to detect it,” not that “there is no advantage.”

A lack of statistical significance is not evidence of real-world equivalence in sports performance. That distinction matters enormously in elite competition, where medals are decided by margins too small for most studies to reliably detect.

Putting It All Together

So what does the BJSM study actually tell us?

It shows that manipulating adult hormone levels changes recreational fitness. That’s interesting. It’s useful. It’s real physiology. But it does not answer what happens when years of elite training collide with biological ceilings set by development. Those are different questions—and confusing them is where much of the public debate goes wrong.

Suppressing testosterone in adulthood can meaningfully shift recreational performance because recreational outcomes are strongly influenced by current physiology: hemoglobin levels, muscle mass, recovery, and short-term training response. Elite sport, by contrast, is decided less by day-to-day hormone levels and more by structural capacities established during development.

Traits shaped during puberty—heart size, skeletal geometry, limb proportions, muscle architecture—largely determine how much performance can ultimately be extracted through years of intense training.

Hormone therapy may change where someone falls in the middle of the distribution, but it does not erase the developmental ceiling. And elite competition is decided at that ceiling, not in the middle.

That is the distinction this literature—and much of the media coverage citing it—continues to miss:

Recreational overlap between sexes does not predict overlap at the elite level.

Adult hormone levels matter, but training is an even stronger determinant of performance.

Extreme training reveals performance ceilings, and those ceilings differ by sex. With equal training, the best biological female athletes have not surpassed the best biological male athletes in the same sport.

That isn’t ideology. It’s how distributions work. It’s how physiology works.

None of this is a statement about human worth. Biology isn’t a value judgment; it’s simply biology. Women aren’t “lesser” athletes because they don’t match male records. They compete within a different physiological category.

As I’ve written before, Faith Kipyegon doesn’t need to run a sub-4:00 mile to be extraordinary. She already is. Her performances are remarkable precisely because they represent the limits of female physiology. Different does not mean inferior. It just means different—which is exactly why female athletes have a distinct competitive category.

The issue surrounding transgender athletes is not whether they have a right to participate in sports, it’s how competition is classified. Sport already relies on classification everywhere else—age groups, weight classes, Paralympic categories—because without them, competition stops being fair or meaningful. Sex categories exist for the same reason.

The point here isn’t to single anyone out or to attack any group. It’s simply to keep the science honest. Studying how testosterone suppression and cross-sex hormones affect basic fitness in recreational or military populations has value. But it does not tell us what happens under elite training conditions, and it should not be used to shape policy for high-level sport. Those are different physiological worlds, and pretending otherwise only muddies the debate.

If we want evidence that genuinely informs elite sport policy, we need studies that actually examine elite performance—not just everyday fitness.

As always, this isn’t about one paper or one controversial topic. I critique questionable claims, misleading headlines, and overstated conclusions wherever they appear. If you enjoy this kind of deep dive into how science gets interpreted—and misinterpreted—you can find more at Beyond the Abstract.

If you enjoyed this free article, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a recurring or one-time donation below to show your support. Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication, and your help is greatly appreciated.

Really helpful, especially for me as I got the conclusion correct but missed the details of why the study was wrong about its claimed conclusion.

Can we also assume that the participants knew the purpose of the study? It would be helpful - and telling - to see the informed consent.