The Queering of Physical Therapy Education

Activists are reshaping physical therapy into a field that prioritizes queer ideology over science and patient care.

Reality’s Last Stand is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support.

About the Author

James L. Nuzzo, PhD, is an exercise scientist and men’s health researcher. Dr. Nuzzo has published over 80 research articles in peer-reviewed journals. He writes regularly about exercise, men’s health, and academia at The Nuzzo Letter on Substack. Dr. Nuzzo is also active on X @JamesLNuzzo.

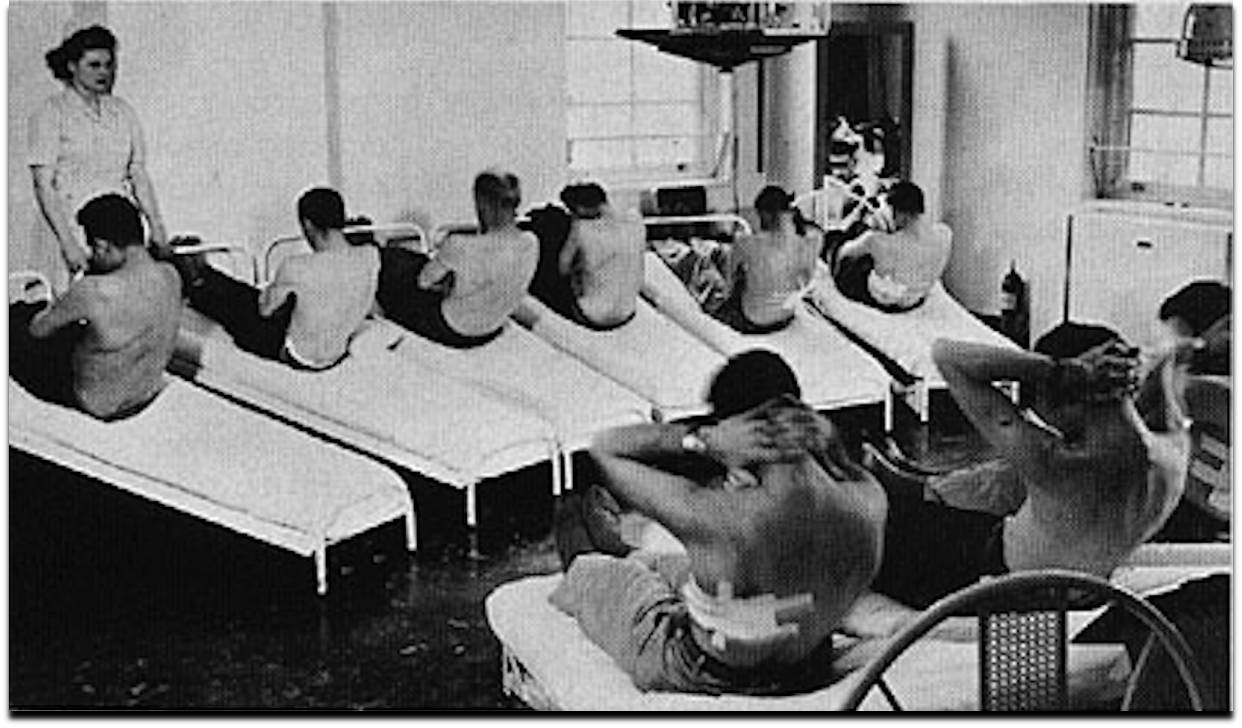

Physical therapists are healthcare professionals who examine, diagnose, and treat movement dysfunction. In the United States, modern physical therapy arose out of the poliomyelitis epidemics and two world wars. During wartime, soldiers returning from the front lines often suffered from physical injuries and impairments that required rehabilitation. The primary goal of physical therapy was to restore physical function—either to return soldiers to combat or to help them reintegrate into civilian life as fully as possible. Because these soldiers were men, physical therapy began as a predominantly female profession.

Following the wars, physical therapy techniques were expanded to serve the broader disabled population. As demand grew, the need for trained professionals increased. To meet this need, university programs and license exams were developed to credential practitioners.

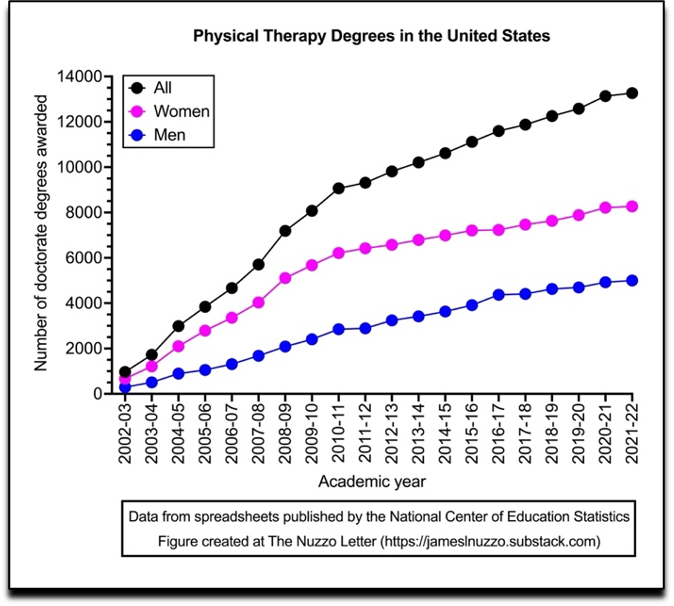

Today in the United States, physical therapy is primarily a doctoral degree program. The number of students earning doctorates in the field has increased substantially over the past 20 years. In the early 2000s, fewer than 4,000 physical therapy doctorates were awarded annually. By the 2021–22 academic year, that number had risen to over 13,000—with approximately 62 percent of those degrees awarded to women.

The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) is the professional organization responsible for setting competency standards and learning objectives for the tens of thousands of physical therapy students enrolled in doctoral programs across the nation. Like many allied health organizations, the APTA has embraced “identity politics” and the broader diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) movement.

The application of DEI and identity politics to health education, clinical practice, and policy is what I refer to as “Woke medicine.” I define Woke medicine as a philosophy of healthcare, rooted in critical theory, which holds that individual health is largely—if not entirely—determined by unjust power structures in society. According to this view, certain social and environmental factors disproportionately affect individuals based on their demographic identity, leading to unequal health outcomes among different groups. The goal of Woke medicine, then, is to raise awareness of these perceived injustices and to improve health outcomes among DEI-designated groups by addressing “structural factors” or the “social” and “political determinants” of health.

The APTA is no newcomer to DEI or Woke medicine. Earlier this year, Do No Harm—an organization dedicated to keeping identity politics out of medical education, research, and clinical practice—reported that APTA scholarships discriminated against applicants based on race and ethnicity. They also noted that the APTA offers a “DEI certificate” and that its continuing education content is “replete with lessons in DEI principles and strategies for physical therapists to advance DEI in their workplaces.”

Based on its investigation, Do No Harm concluded that the APTA “envisions itself as a political actor, and uses its position with the physical therapy profession to advance a radical racial ideology through its initiatives, courses, and scholarships."

That conclusion is difficult to dispute, especially considering two papers published last year in the APTA’s flagship journal, Physical Therapy, which focused on the “queering” of the profession.

The first author of the papers was Joe Tatta—CEO of the Integrative Pain Science Institute and an advocate for “health equity,” “disability justice,” “social justice,” and what he calls “pain liberation.” According to Tatta, improving care for painful conditions is “nothing short of a liberation movement.”

One of his papers, titled “Queering the Physical Therapy Curriculum: Suggested Competency Standards to Eliminate LGBTQIA+ Health Disparities,” outlines resources to “develop and implement competency standards in [Doctor of Physical Therapy] programs while providing an overview of LGBTQIA+ health disparities.” In a supplementary file not included in the print version, Tatta categorized 28 student competency standards and their related learning objectives into four broad areas of LGBTQIA+ healthcare: theories and concepts, physical health concerns, mental health concerns, and physical therapy specific concerns.

Tatta encourages educators to use these standards and objectives to “queer” their physical therapy curricula—something he defines only vaguely as “an approach educators use to implement culturally responsive teaching pedagogy.” He also notes that the competencies are “in accordance with the American Physical Therapy Association’s online resources on diversity, equity, and inclusion; cultural competence in physical therapy; and the PT Proud Introduction to LGBTQ+ Competency: Handbook for Physical Therapy.”

Tatta’s second paper titled, “A Call to Action: Develop Physical Therapist Practice Guidelines to Affirm People Who Identify as LGBTQIA+,” calls on the APTA to develop guidelines for affirming LGBTQIA+ patients. The paper proposes guidelines for physical therapy practice with LGBTQIA+ patients, along with a glossary of LGBTQIA+ terms. However, the glossary was again not included in the print version of the paper but was instead presented in an online supplementary file.

Here, I aim to highlight some of the specific problems with Tatta’s ideas. These include a misguided focus on health “disparities,” taking non-evidence-based cheap shots at other physical therapists, coercing physical therapists into practicing affirmative care, promoting biological denialism (e.g., in the case of transgender athletes), and unnecessarily injecting political activism into the physical therapy profession.

Health “Disparities” and “Inequalities”

One of Tatta’s key arguments for providing LGBTQIA+ individuals with special consideration in physical therapy education and care is that they tend to have worse health outcomes than non-LGBTQIA+ individuals. Tatta refers to these group differences as “disparities” and “inequalities.”

Exploring health differences across demographic groups is standard epidemiology and is useful for understanding societal patterns in health. Learning such information with regard to LGBTQIA+ individuals is probably the most (and perhaps only) appropriate recommendation that Tatta makes.

The issue with Woke medicine lies not in acknowledging these health differences, but in how the causes of these differences are interpreted and what actions are taken in response. Tatta adheres to queer theory, which is part of critical theory. Consequently, he believes that poor health outcomes among LGBTQIA+ individuals are primarily, if not entirely, the result of unjust power dynamics in society. This belief explains why Tatta focuses more on social and environmental factors—such as “affirming,” “bias,” “systemic harassment and discrimination,” and “lack of cultural competency”—than on biological and psychological explanations. The adoption of queer theory is also why Tatta believes that physical therapy students should learn to “[i]dentify the ways gender, power, privilege, and oppression play out across a range of cultures and human experiences,” and why he recommends that students, educators, and practitioners become political advocates for the LGBTQIA+ community and strive to “eliminate LGBTQIA+ health disparities” by acting on structural and governmental factors that impact health.

Tatta’s adoption of the health inequalities framework also leads to the odd, though common, practice of lumping all LGBTQIA+ persons together. This approach is used throughout public health literature and reflects political rather scientific motives. Many biological and medical distinctions exist within the LGBTQIA+ community—lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, for example, may have very different health profiles. From a physical therapy perspective, a lesbian surely shares more in common with a heterosexual woman than with a gay man. Similarly, a transgender individual undergoing hormone treatments does not present the same clinical needs as the average gay or lesbian person.

Lumping LGBTQIA+ persons together is also problematic because some members of this cohort do not appear to have worse physical health outcomes than non-LGBTQIA+ persons. One study found that individuals aged 50 and older who identified as LGB had higher rates of overall disability than their heterosexual counterparts. However, closer inspection of the data revealed that the primary driver of the difference in disability was in patient mental health not physical health (e.g., arthritis). In fact, a study that Tatta cited to support his claim that LGBTQIA+ persons have a higher physical disability rates than non-LGBTQIA+ persons did not even look at physical health; it was concerned with mental health. Physical health, not mental health, is the aspect of patient wellbeing that is most within the scope of practice of physical therapists.

Cheap Shots at Colleagues

Tatta’s belief that critical theory-based factors are the drivers of health “disparities” among LGBTQIA+ persons led to a series of cheap shots taken at other physical therapists. Apparently, physical therapists themselves are part of the problem.

First, Tatta said that physical therapists should “listen to and learn from patients in the LGBTQIA+ community.” However, he provided no evidence that physical therapists are not already listening.

Second, Tatta implied that only through the proposed curriculum would physical therapists "learn to provide compassionate, high-quality, and culturally competent care." Again, he offered no evidence that physical therapists are not already delivering care that is both compassionate and competent.

Third, Tatta recommended that physical therapists “educate themselves to avoid unconscious and perceived biases.” Yet, no evidence was presented showing that such biases exist among physical therapists.

Regrettably, cheap shots like these are neither specific to Tatta nor to the field of physical therapy. They are common within Woke academia.[1]

Supervising Religious Physical Therapists

An additional cheap shot taken by Tatta at other physical therapists—one that I believe warrants public ridicule of both Tatta and the APTA—is Tatta’s suggestion that religious physical therapy students should be supervised when providing care to LGBTQIA+ individuals. The associated learning objective reads as follows:

Describe [to students] why religious physical therapists may need to consult with colleagues and undergo supervision to ensure that religious beliefs do not interfere with their practice and patient outcomes for people who identify as LGBTQIA+.

As an atheist, I have no personal stake in defending religion. However, requiring a religious student or practitioner to be supervised while providing care is discriminatory and otherwise problematic for several reasons.

First, how would this supervision occur in an education setting? Would students be required to identify their religious affiliation by raising their hands or having religious symbols printed on their student identification cards? Would Jews, Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, agnostics, and atheists then practice delivering treatment in separate sections of the room? Would the atheists—with their implied moral superiority—hover over their religious colleagues, monitoring for misuse of terms in Tatta’s LGBTQIA+ glossary?

Second, Tatta never explained how a therapist’s religiosity impacts their treatment of LGBTQIA+ persons. He did not, for example, cite any survey that asked religious and non-religious physical therapists about their views on treating LGBTQIA+ persons, nor did he provide evidence that health outcomes for LGBTQIA+ individuals are worse when treated by religious therapists. In fact, given the high prevalence of religiosity in the U.S.—with three out of every four physical therapy students identifying as religious—religious physical therapists have presumably provided compassionate and effective care to LGB individuals for many years.

Third, physical therapists are not the only allied health professionals who deliver healthcare to LGBTQIA+ individuals. Consequently, if Tatta believes that religious physical therapists are not qualified to care for LGBTQIA+ individuals, presumably this belief then also applies to religious occupational therapists, dietitians, exercise physiologists, etc.

Demanding Affirmative Care

One of Tatta’s key messages is that physical therapists should be trained to affirm the sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression of LGBTQIA+ patients. According to Tatta, “[a]ffirmative practice is an approach to health care that validates and supports the identities stated or expressed by those served.” He further explains that “[g]ender-affirming care is any intervention that supports an individual in aligning their gender identity to their well-being.”

Tatta advocates for affirmative care based on the belief that failing to affirm the sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression of LGBTQIA+ patients leads to worse health outcomes. Here, Tatta cites a study in the field of psychotherapy that found “perception of a therapist’s affirmative practices is associated with psychological well-being…” From this, Tatta concludes that physical therapists should “not tell their patients that they can change their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.”

Tatta’s stance on affirmative care has several major issues.

First, much of what Tatta discusses regarding affirmative care (e.g., the psychology of gender identity) falls outside the scope of physical therapy. In fact, at one point, after dousing readers with a series of debatable claims, Tatta finally acknowledges that referrals to mental health services may occasionally be necessary for LGBTQIA+ patients.

Second, Tatta, like others who push transgender ideology, conflates affirmation and empathy. By conflating these two concepts, Tatta implies that therapists who do not affirm LGBTQIA+ patients do not have empathy for them. This sly intellectual trick amounts to a sort of passive bullying of colleagues into practicing affirmative care out of fear of being called unempathetic. However, no clinician should be required to validate a patient’s belief if they feel it is misaligned with reality. For example, if an obese patient believes their excess weight is not a health issue, a physician is not obligated to affirm that belief as correct. Doing so would constitute professional negligence. Similarly, in physical therapy, if a patient believes that the cause of their back pain is X, but the scientific literature and the therapist’s clinical experience suggest that the cause is Y, the therapist is not required to affirm the patient’s misguided belief. A physical therapist can empathize with a patient’s life challenges while still adhering to biological reality. Furthermore, Tatta offers no evidence to suggest that physical therapists currently lack empathy for LGBTQIA+ patients.

Third, Tatta’s recommendation that physical therapists practice affirmative care—defined as “any intervention that supports an individual in aligning their gender identity to their well-being”—implies that therapists should suspend their independent medical judgments and support “any” intervention that a transgender individual wishes to pursue. This suggestion is concerning because “any” could include interventions that expose patients to additional health risk, and LGBTQIA+ individuals are already known to have higher rates of mental health issues, including suicidal thoughts.

Fourth, prioritizing gender identity over biological sex in physical therapy poses a problem because physical health issues are often patterned by sex. For example, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, multiple sclerosis, and arthritis are all known to be more prevalent in the female than male sex in humans. Changing one’s gender identity likely does not alter one’s risk profile for these conditions.

Controlling Language to Ensure Affirmative Care

The idea that affirmation is essential to physical therapy for LGBTQIA+ individuals led Tatta to take on the role of sheriff of physical therapy’s thought and language police. In addition to stating that physical therapists should not tell their patients that they can change their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression, Tatta published the aforementioned glossary of LGBTQIA+ healthcare terms. The stated purpose of this glossary is to “enhance cultural awareness and sensitivity” among physical therapists and ensure they are “better informed about the unique needs and experiences of LGBTQIA+ people.”

Example terms in the glossary include “ally,” “deadnaming,” “genderqueer,” “health equity,” “intersectionality,” “institutional abuse,” “neopronouns,” “outing,” “third gender,” and “transmisogyny.” The word “patriarchy” also appears in the list, which is ironic considering that physical therapy has been a female-dominated profession throughout its history.[2]

The term “pronoun” was also included in the glossary, and Tatta’s definition of it reveals authoritarian undertones. He explains that the term “pronoun” is now preferred over “preferred pronoun” because the latter “suggests a preference that others can choose to ignore or not.” In other words, Tatta’s stance is that students must use a patient’s preferred pronoun. This explains why one of Tatta’s student learning objectives is “the appropriate use of pronouns and terminology in respectful communication with members of the LGBTQIA+ community.”

Biology, Treatments, and Transgender Athletes

Another issue with Tatta’s papers is the lack of attention given to anatomy, physiology, and epidemiology—the essential topics that would help physical therapy students deliver effective treatments to LGBTQIA+ patients. Tatta did not discuss common physical health problems or their prevalence rates among LGBTQIA+ persons. Should students expect to see many cases of neck pain in LGBTQIA+ persons? What about arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, rotator cuff injuries, Achilles tendinopathy, fibromyalgia, or multiple sclerosis? Tatta does not provide such information.

Additionally, Tatta does not address whether being LGBTQIA+ impacts treatment effectiveness. Does a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity have implications for whether heat, cold, massage, stretching, traction, or strength training are effective in resolving their physical ailments? Tatta does not engage with such questions, likely because there is little physiological basis for why physical therapy treatments would differ based on gender identity. Oddly, Tatta also devotes little discussion to surgeries and hormone treatments in transgender persons and their implications for physical therapy care.

The topic of transgender athletes, also included in the student competency standards and learning objectives, reflects another area where information on biology was denied or ignored. According to Tatta, “[b]eing forced to participate in sports or physical activity according to assigned sex at birth rather than gender identity can exacerbate gender dysphoria, causing distress for transgender individuals.” Tatta then describes how exclusion from sports can contribute to social isolation, homophobia, discrimination, depression, and low self-esteem among LGBTQIA+ individuals. Tatta, like others who believe that men should be allowed to compete in women’s sports, overlooks the potential impact of such a policy on the mental and physical health of the female athletes.

Furthermore, Tatta referenced the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) policies on fairness, inclusion, and non-discrimination based on gender identity, which includes the “no presumption of advantage” clause. However, the IOC’s “no presumption of advantage” position is out of sync with scientific knowledge of sex differences in physical performance. Thus, physical therapy students who are taught the IOC’s position will certainly learn something—but it won’t be biology.

Political Activism

Interest in politics is likely not a factor that motivates most students to enter the field of physical therapy. Yet, Tatta argues that physical therapists ought to become activists on behalf of the LGBTQIA+ community. The progressive platitude, “call to action,” which appears in the titles of multiple papers written by Tatta, is a signal that such political activism is central to his work.

Regarding physical therapists’ political involvement, Tatta wrote:

“Physical therapists [should] support jurisdictional, state, and federal policies aimed at improving the health and well-being of LGBTQIA people.”

“[Physical therapists] need to advocate for laws that increase access to quality care for marginalized communities including those addressing LGBTQIA+ individuals.”

“There is a role for physical therapists to promote policy and research agendas to protect the health of people who identify as LGBTQIA+. Political determinants affect the health-related quality of life of people who identify as LGBTQIA+. [Doctorate of physical therapy] programs should consider including educational content that raises awareness of the political determinants impacting the LGBTQIA+ community. This includes how physical therapists can be allies who promote policy and research agendas that protect the health of people who identify as LGBTQIA+.”

In other words, Tatta’s papers are not meant to spark only theoretical classroom debates. They are intended to influence education, clinical practice, and public policy. For example, when Tatta suggests that religious physical therapists should be supervised when treating LGBTQIA+ patients, or that students should master a glossary of LGBTQIA+ terms, these suggestions are to be interpreted literally. When Tatta advocates for increased political content in physical therapy education, students can expect that a lecture on scoliosis might be interrupted by an “important” political announcement about an LGBTQIA+ event on campus. If attending the event is not made mandatory, it would likely be presented as an opportunity for “extra credit” or some other ploy to turn the students into activists.

Conclusion

In recent years, the APTA, like many other organizations, has adopted critical theory and promoted Woke medicine. Tatta’s papers, which seek to “queer the physical therapy curriculum,” represent an effort to institutionalize these ideologies into education and clinical practice. However, queer theory will not resolve anyone’s back pain or tendinopathy; it will only divide the physical therapy profession into political camps.

All Tatta needed to do was write a paper on the biology, psychology, and epidemiology of health in LGBTQIA+ individuals and explain the treatments that are most likely to restore movement in these patients. But Tatta, with seemingly a nod of approval from the APTA, chose a different path. To appear progressive and empathetic, they embraced a medical theory that misattributes the causes of health issues, took cheap shots at colleagues, recommended controlling aspects of speech and clinical practice, and prioritized politics over biology. In short, they acted like authoritarians—an ironic stance given that the nation’s physical therapy profession was founded, in part, to help combat collectivist tyranny around the world.

Thank you for supporting Reality’s Last Stand! If you enjoyed this article and know someone else you think might enjoy it, please consider gifting a paid subscription below.